Acute respiratory infections in the EU/EEA: epidemiological update and current public health recommendations

Key messages

- Several viral and bacterial respiratory pathogens are expected to continue co-circulating at variable levels during the coming months, and contribute to increased morbidity and mortality during this period. This is typical of every winter season. Widespread implementation of non-pharmaceutical measures during the COVID-19 pandemic led to very low circulation of both viral and bacterial respiratory pathogens which resulted in reduced population immunity. This may exacerbate the respiratory disease burden this winter, particularly amongst those with few or no pre-existing exposures, such as young children.

- Primary care consultation rates for respiratory illness monitored through established sentinel surveillance systems have been gradually increasing as expected in the EU/EEA since September 2023. Of 23 countries using the Moving Epidemic Method (MEM) thresholds, Influenza-like-illness (ILI) rates were above baseline levels in five countries and Acute Respiratory Infection (ARI) rates were above baseline levels in three countries. Rates of severe acute respiratory infection (SARI) monitored through sentinel surveillance at hospital sites reported by six countries remain at or below rates observed at the same time last year.

- SARS-CoV-2 has continued to circulate at higher levels than seasonal influenza and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), with severe disease predominantly affecting those aged 65 years and above. RSV activity has been steadily increasing over the past week, with the highest burden among children aged 0–4 years. Seasonal influenza activity remained at a low level, although some countries report that they observe increased influenza activity and geographical spread. Influenza activity is expected to increase in the coming weeks, although it is not yet possible to determine how severe this season will be and whether currently available vaccines will be well matched with circulating strains.

- Since October 2023, increases in respiratory infections due to Mycoplasma pneumoniae were reported by six EU/EEA countries [1-5]. M. pneumoniae is not notifiable in most EU/EEA countries, leading to limited available information regarding diagnosed cases, proportion of detections amongst respiratory laboratory samples, or historical detection data. As a result, country-level or historic comparisons should be made with caution.

- Following substantial increases in all-cause mortality levels during the COVID-19 pandemic, all-cause mortality in Europe (both for the total population and in all age groups) returned to expected, pre- pandemic levels by spring 2023. Currently, pooled estimates of all-cause mortality show that all-age mortality is at baseline, with an elevated level of mortality observed in the age group of 65 years and above. This age-specific increase in mortality is in line with historic increases observed at this time of year.

- Member States should prepare for the possible need to increase emergency department and ICU capacity (in terms of adequate staffing and bed capacity), for both adult and paediatric hospitals. Hospital administrators and managers should ensure that resources, such as medical/nursing staff and equipment, are also available. Ensuring healthcare staff are trained to implement appropriate infection prevention and control (IPC) measures will contribute to reducing the burden in healthcare settings and avoid outbreaks within these settings, including in long-term care facilities (LTCFs).

- Clinicians should be reminded that, when indicated, the early use of antiviral treatments for COVID-19 and influenza may prevent progression to severe disease in vulnerable groups. RSV prophylaxis for infants can be considered in accordance with national guidelines.

- It remains essential for Member States to continue developing, strengthening and sustaining resilient population-based integrated surveillance systems, including genomic surveillance, for influenza, COVID- 19, and potentially other respiratory virus infections (such as RSV or new viral diseases of public health concern). Monitoring severe disease burden through hospital surveillance systems using SARI case definitions remains critical to assess the burden.

- Active promotion of vaccinations against seasonal influenza, COVID-19 and RSV in accordance with national recommendations is already ongoing and should continue in all Member States. Vaccination remains the most effective measure for preventing COVID-19 and influenza infection from progressing to severe disease.

- For more effective promotion of vaccination uptake of the recommended vaccines, countries can consider the ‘5Cs diagnostic model for vaccination’ (Confidence, Complacency, Constraints, Collective Responsibility and Calculation).

- Risk communication activities for the public should be implemented, including targeted guidance for risk groups, healthcare workers and caretakers of vulnerable groups. Key recommendations include vaccination according to national recommendations, staying home when ill, respiratory etiquette and good hand hygiene, appropriate ventilation of indoor spaces, and promotion of appropriate public health and social measures (PHSM) (also called non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs)). People with high risk for severe disease (as well as their caretakers and close contacts) should consider using a face mask when in crowded public spaces.

Global situation

This report describes the current epidemiological situation of acute respiratory infections in the EU/EEA countries and provides updated ECDC recommendations for mitigating their impact.

Countries in the northern hemisphere experience winter surges of acute respiratory infections caused by several pathogens, including SARS-CoV-2, influenza, RSV, and other seasonal virus and bacteria. The co-circulation of these pathogens increases pressure on healthcare systems, with outbreaks of respiratory infection leading to increased primary care consultations and hospitalisations, particularly for patients with comorbidities and risk factors for severe outcomes. Influenza and RSV have caused the greatest seasonal impact in terms of morbidity, mortality, and work/school absenteeism in interpandemic years, whereas SARS-CoV-2 caused the largest impact between 2020 and 2023 without a clear seasonal pattern.

Increasing trends of several respiratory pathogens are currently being documented in various countries across the northern hemisphere. Since early autumn 2023, seasonal flu activity and flu hospital admissions continue to increase in most parts of the United States and Canada [6,7]. Additionally, the United States has observed a modest increase in childhood pneumonia cases due to a range of respiratory pathogens, including Mycoplasma pneumoniae. However, overall rates of pneumonia are currently largely consistent with pre-pandemic years [8]. In early November, China reported a nationwide increase in the incidence of respiratory diseases, primarily affecting children and attributed to the co-circulation of multiple known pathogens, particularly M. pneumoniae [9].

According to information shared in a press conference held on 10 December 2023 [10], the overall volume of diagnosis and treatment of children's respiratory diseases in the country was decreasing, thereby reducing the burden on paediatric hospitals. There was an increase in recent weeks in rates of influenza-like illness in sentinel hospitals across China [11], however, levels were below the peaks observed in the winter of 2022/2023. An increase in M. pneumoniae infections to levels similar to pre-pandemic seasons has also been observed in South Korea[12]. Increases in ILI have also been reported from Japan, with an earlier start of the season compared to previous years (including pre-pandemic seasons) [13].

Epidemiological situation in the EU/EEA as of week 48

As outlined in the guidance document ‘Operational considerations for respiratory virus surveillance in Europe’ [14], ECDC performs integrated surveillance of influenza, COVID-19, and other respiratory virus infections in the EU/EEA. Representative sentinel surveillance systems in primary and secondary care based on well-defined case definitions (ILI/ARI/SARI) are the central component of acute respiratory infection surveillance. ECDC publishes routinely collected data weekly through the European Respiratory Virus Surveillance Summary (ERVISS) [15].

Additionally, countries are encouraged to report unusual events or clusters of respiratory infections not monitored by routine surveillance through EpiPulse.

Respiratory virus activity in the community

Medical consultation rates for respiratory illness have been increasing in primary care settings since September. Of 23 countries using the Moving Epidemic Method (MEM) thresholds to detect significant upsurges in week 48, ILI rates were above baseline levels in five countries (Belgium, Denmark, Greece, Latvia, Luxembourg) and ARI rates were above baseline levels in three countries (Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania). This indicates respiratory pathogen activity of low to medium level in a subset of EU/EEA countries.

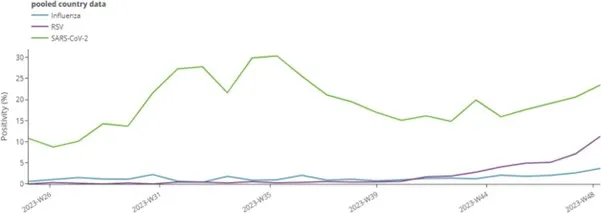

In week 48, test positivity data for patients presenting to primary care sentinel sites showed that SARS-CoV-2 was circulating at higher levels than RSV and seasonal influenza (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Aggregate weekly sentinel primary care pooled test positivity for seasonal influenza, RSV and SARS-CoV-2 in the EU/EEA, week 25/2023-week 48/2023*

* Number of countries reporting data can vary between reporting weeks. In week 48, 14 countries reported data for SARS-CoV-2, 15 countries reported for influenza and 12 countries reported data for RSV. Please see ERVISS for more information on number of countries reporting every week [15].

The proportion of acute respiratory infections due to SARS-CoV-2 has remained high (above 10%) since week 25, with a slight upward trend since week 40. In week 48, the pooled test positivity in primary care was 24% (median 19%, data from 14 countries) (Figure 1). At the country level, increasing and decreasing trends for SARS-CoV-2 test positivity were observed during this period, indicating regional variability. It is important to note that sentinel system sizes and testing numbers vary significantly between countries, influencing the precision of the trend analyses. These figures are however consistent with SARS-CoV-2 detections observed among respiratory specimens collected outside of the surveillance sentinel sites.

In addition to SARS-CoV-2, infections due to the respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) have been consistently increasing in the past few weeks. At EU/EEA level, the pooled test positivity in primary care was 11% (median 3%, data from 12 countries) in week 48 [15]. Overall, RSV circulation intensified later than the previous year and positivity is still at less than half the maximum reached last year.

Seasonal influenza activity remains at a low level, although qualitative assessments made by countries indicate increasing intensity of influenza activity and geographical spread in a number of countries [15]. Overall, the pooled test positivity in primary care was 4% in week 48 (median 3%, data from 15 countries), with three countries (Estonia, Greece, Lithuania) exceeding 10% test positivity in sentinel primary care. All three influenza virus types/subtypes (A(H1)pdm09, A(H3) and B) are co-circulating. It is not yet possible to determine whether these initial increases represent the start of the 2023/24 influenza season as there isn’t a clear dominant virus subtype, nor sustained increases confirmed for a sufficient number of weeks.

Surveillance of severe disease

Rates of SARI cases are comparable to those observed during the same period last year. Two countries (Germany and Spain) have reported increases in SARI rates in the past three weeks in the 0–4-year-old age group. However, current data availability regarding disease severity from SARI systems is limited, as only six countries have reported syndromic SARI data to ECDC since week 40/2023. Additionally, it is important to note that reporting delays in SARI data are expected, as some information related to cases may only be available after discharge and clinical data collection can often include resource-intensive elements [16].

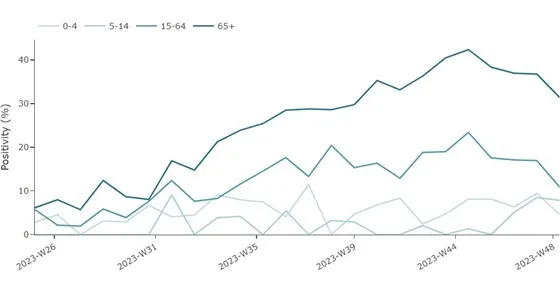

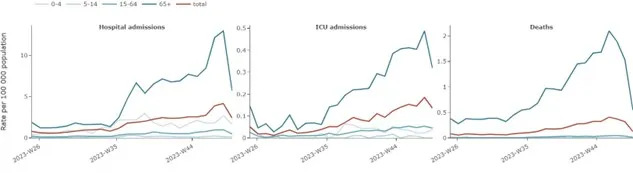

An increase in pooled SARS-CoV-2 test positivity among SARI cases were observed between week 29 and week 44 in people aged 15–64 years and in those 65 years and above, with a mixed picture at the country level (six countries reporting data) (Figure 2). However, a decreasing trend has been observed for these age groups since week 44, which may be partially attributed to reporting delays. At the EU/EEA level, non-sentinel COVID-19 hospital admissions, ICU rates and mortality rates have gradually increased since week 36, mirroring the data reported from sentinel systems (Figure 3). The decreasing trend observed in non-sentinel COVID-19 hospital admissions, ICU rates and mortality rates over the last one to two weeks is most likely also attributable to delayed reporting.

Figure 2. Proportion of COVID-19 cases among people hospitalised with severe infections by age group, weeks 25-48/2023 *

*Number of countries reporting data can vary between reporting weeks. In week 48, 4 (Ireland, Germany, Malta, Spain) countries reported data for SARS-CoV-2 shown in the figure above. Note that data from Ireland is for cases ≥15 years of age.

Figure 3. Rate of severe COVID-19 cases, by week, age and clinical outcome (non-sentinel sources), week 25/2023-week 48/2023*

*Number of countries reporting data can vary between reporting weeks and between age groups. In week 48 for total age group, 11 countries reported data for SARS-CoV-2 hospital admissions, 10 countries reported data for ICU admissions and 16 countries reported data on deaths.

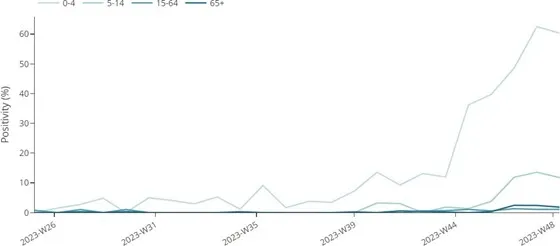

Increasing trends in RSV test positivity were observed in two (Germany and Spain) out of four countries reporting RSV data from SARI systems over the past three weeks (Figure 4). Test positivity reached a plateau in the last week which is most likely due to a reporting delay. Test positivity remains highest for the 0–4 years age group (60%), and the 5–14 years age group (12%). Non-sentinel RSV hospital admissions remained high in the 0–4- years age group in two (Ireland and Malta) out of four countries reporting data in week 48.

Figure 4. Proportion of samples positive for RSV among patients with severe respiratory infections, by age group, weeks 25-48/2023*

*Number of countries reporting data can vary between reporting weeks. In week 48, 4 (Ireland, Germany, Malta, Spain) countries reported data for SARS-CoV-2 shown in the figure above. Note that data from Ireland is for cases ≥15 years of age.

In week 48, test positivity for seasonal influenza in sentinel SARI systems remains low at 3%. Non-sentinel hospital admissions, ICU admissions and deaths due to influenza also remain low.

Analysis of all-cause mortality data in Europe is conducted by EuroMOMO [17]. Following substantial increases in all-cause mortality levels during the COVID-19 pandemic, all-cause mortality in Europe (both for the total population and in all age groups) returned to expected, pre-pandemic levels by spring 2023. In week 48, 2023, pooled estimates of all-cause mortality for 25 participating European countries or subnational regions showed that all-age mortality was at a baseline, with an elevated level of mortality observed in the age group of 65 years and above. This age-specific increase in mortality is in line with historic increases observed at this time of the year [17]. It is important to note that all-cause mortality can be influenced by multiple factors unrelated to outcomes due to communicable disease, such as environmental factors, which include extreme weather conditions.

Virological surveillance data

ECDC works closely with WHO to compare assessments and classifications of circulating SARS-CoV-2 variants. The aim of classification is to communicate information about variants which emerge that may impact the epidemiological situation. ECDC and WHO utilise three categories of variant classification with increasing levels of concern: variant under monitoring (VUM), variant of interest (VOI) and variant of concern (VOC). WHO updated its variant classification criteria in March 2023 (with a minor modification in October) [18]. The classification used by WHO is closely aligned with that used by ECDC [19]. Both organisations focus on classification that includes major evolutionary steps, with a more specific focus on variants requiring major public health interventions. The distribution of these variants is displayed in ERVISS [15].

For the two-week period to week 47, 2023, the estimated distribution (median proportions from 16 countries) of variants of concern (VOCs) or variants of interest (VOIs) was 51% for XBB.1.5+F456L, 26% for BA.2.86 and 6% for XBB.1.5. The proportion of BA.2.86 has been growing, with XBB.1.5-like+F456L and XBB.1.5 showing a decreasing trend.

All three influenza virus types/subtypes (A(H1)pdm09, A(H3) and B) are co-circulating, currently. So far, influenza A subtypes are predominant in sentinel and non-sentinel virological surveillance data. During weeks 40–48, 2023, 83 A(H1)pdm09, 34 A(H3) and six B/Victoria viruses from sentinel and non-sentinel sources were genetically characterised. Of the A(H1)pdm09 viruses, 38 were reported as clade 5a.2a and 45 were subclade 5a.2a.1 which is

the clade included in the northern hemisphere 2023/24 influenza season. Of the A(H3) viruses, one was reported as clade 2a.3a and 33 were subclade 2a.3a.1, which is different from the northern hemisphere vaccine component and similar to the new virus recommended for inclusion in the 2024 southern hemisphere influenza season vaccines. All the B/Victoria viruses were reported as subclade V1A.3a.2 which is the clade included in the northern hemisphere influenza season. Given current low levels of influenza circulation, it is not possible to confirm how the distribution of circulating influenza types and subtypes will evolve, nor which strains or clades will dominate later this winter.

WHO recommends that trivalent vaccines for use in the 2023/24 influenza season in the northern hemisphere contain the following (egg-based and cell culture or recombinant-based vaccines respectively): an A/Victoria/4897/2022 or A/Wisconsin/67/2022 (H1N1)pdm09-like virus (subclade 5a.2a.1); an A/Darwin/9/2021 or A/Darwin/6/2021 (H3N2)-like virus (clade 2a); and a B/Austria/1359417/2021 (B/Victoria lineage)-like virus (subclade V1A.3a.2) [20].

Other pathogens

Several other respiratory pathogens are expected to co-circulate during the coming winter months, contributing to increased morbidity. These can include a range of viruses (such as adenoviruses, metapneumovirus, parainfluenza viruses, rhinoviruses and seasonal coronaviruses) and bacteria (such as Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Streptococcus pyogenes, Haemophilus influenzae and Bordetella pertussis). Some of these circulate throughout the year with no strong seasonal trend, while others may have more seasonal patterns and their prevalence can vary with seasons. For pathogens not under routine surveillance in EU/EEA countries, it is difficult to make an EU-wide assessment of their specific impact. When assessing increases in transmission of other pathogens it should be noted that this period follows the widespread implementation of non-pharmaceutical measures and the very low circulation of respiratory pathogens during the COVID-19 pandemic, which may result in reduced population immunity, particularly amongst those with little or no pre-existing exposures, such as young children. Concurrent resurgence of pathogens that have circulated at lower levels in recent years may contribute additional pressures on healthcare systems this winter.

Since October 2023, increases in respiratory infections due to Mycoplasma pneumoniae were reported by six EU/EEA countries [1-5]. M. pneumoniae is not notifiable in most EU/EEA countries, leading to limited available information regarding diagnosed cases, proportion of detections amongst respiratory laboratory samples, or historical detection data. As a result, country-level or historic comparisons should be made with caution. M. pneumoniae epidemics occur cyclically in Europe every one to three years [21]. Various factors contribute to this cyclical pattern, such as the decline of population immunity over time or the introduction of new strains into the population. The reported increases are observed following a three-year period of very limited transmission and detection of M. pneumoniae in the EU/EEA during the pandemic and the caveats mentioned above. There are currently no reports of atypical M. pneumoniae strains or resistance to first-line macrolide antibiotics from reporting countries in the EU/EEA.

Testing, monitoring and reporting

EU/EEA Member States are encouraged to establish and expand well-designed, representative population-based surveillance in primary and secondary care to monitor trends in transmission and severe disease. This is outlined in the guidance document, ‘Operational considerations for respiratory virus surveillance in Europe’ [14]. Non-sentinel data are valuable complementary data and should continue to be reported if possible. The most up-to-date surveillance data should be reported to the European Surveillance System (TESSy) on a weekly basis, according to the published reporting protocol [22]. In addition to routine reporting through TESSy, it remains crucial that countries report unusual events or clusters of respiratory infections through EpiPulse.

Considering the current reports of elevated detections of M. pneumoniae in several EU/EEA countries, it remains important to monitor the occurrence of atypical and/or severe forms of disease, or evidence of resistance to antibiotics. Any such information should be reported through EpiPulse.

Currently, only a limited number of countries in the EU/EEA routinely report syndromic SARI and pathogen detection data from secondary care sentinel sites. Secondary care data from representative networks of hospital sites based on established SARI case definitions provide extremely valuable information on severe disease. A number of EU/EEA countries participate in the European SARI Surveillance Network (E-SARI-Net), which aims to strengthen SARI surveillance systems. Member States are encouraged to establish or improve reporting from such systems. Data from hospital laboratories and registry systems currently provide important complementary data and remain essential to assess severe disease while sustainable sentinel systems are being established and expanded.

Where possible, testing for other pathogens, like RSV, should be included in the ARI and SARI sentinel surveillance systems as effective integrated respiratory surveillance systems should provide sufficient data to monitor the intensity of circulation and spread of respiratory viruses, helping to guide control measures and mitigate their impact. As the clinical spectrum for COVID-19, RSV infection, and other respiratory virus infections does not always include high temperature, the ARI case definition is more sensitive than ILI for integrated sentinel surveillance [14]. Countries that choose to extend to ARI are strongly encouraged to continue to collect the number of consultations from ILI patients, to allow the use of the more specific ILI syndromic indicator for monitoring influenza activity and calculation of epidemic thresholds with historical data.

A representative subset of upper respiratory specimens from patients with respiratory symptoms (ARI/ILI/SARI) via primary and secondary care sentinel surveillance should be tested for respiratory pathogens (influenza, SARS-CoV- 2 and others). RT-PCR is the gold standard for laboratory testing for respiratory viruses and multiplex tests are available that can simultaneously test for multiple pathogens (including bacteria). Culture and serology are also used in clinical practice to diagnose other respiratory pathogens, for example serology is used to diagnose M.pneumoniae infections. Self-testing using Rapid Antigen Detection Tests (RADTs) can also be used to quickly detect COVID-19, influenza and/or RSV and ensure appropriate treatment (i.e. antivirals against SARS-CoV-2 and influenza) and the implementation of other public health actions when appropriate. For further details on testing, monitoring and reporting, please refer to the guidance document on integrated Operational considerations for respiratory virus surveillance in Europe [14].

Recommendations for public health actions

Vaccination

Vaccination remains the most effective measure for preventing COVID-19 and influenza infection from progressing to severe disease.

COVID-19

ECDC recommends that COVID-19 vaccination campaigns for the coming months focus on protecting those aged over 60 years and other vulnerable individuals irrespective of age (such as those individuals with underlying comorbidities and individuals with immunocompromised conditions) [25]. In addition, vaccination of healthcare workers should be considered because of their likely increased risk of exposure to new waves of SARS-CoV-2 and their key role in the functioning of healthcare systems [25,26].

Mathematical modelling performed in 2023 indicated that an autumn 2023 vaccination campaign (with an optimistic scenario of high vaccine uptake among individuals aged 60 years and above) was expected to prevent an estimated 21–32% of the cumulative total all-age COVID-19 related hospitalisations across EU/EEA countries until 28 February 2024. [27].

Almost all EU/EEA countries have issued recommendations for autumn 2023 vaccination campaigns, were initiated from September 2023 in some countries. The age cut-offs of national recommendations differ between countries ranging from 50 to 65 years, with COVID-19 vaccination usually recommended to the same age groups as the annual influenza vaccination. Other high-risk groups for which vaccination is recommended include persons aged six months and older with underlying diseases (i.e. chronic respiratory, cardiovascular, liver and kidney disease, diabetes, obesity, chronic neurological disease, immunosuppression) and residents in long-term care facilities.

Preliminary data from the Member State autumn campaigns [28-33] indicate a wide variation in uptake in the recommended age-groups, ranging from 20% to over 70% for one country.

In order to maximise uptake among target groups, countries should carefully consider factors that have previously limited booster vaccine uptake. Communication campaigns providing clear information through trusted people and channels on which groups vaccination is recommended for, why vaccination is important, and the appropriate timing of doses are all key to improving vaccine uptake. Campaigns should also include engagement with healthcare workers, as they are trusted sources regarding information on vaccination. Strategies to facilitate access to vaccination services should also be considered.

Influenza

ECDC recommends promotion of the annual influenza vaccination according to national recommendations, as it remains the single most effective measure for preventing infection and development of severe disease among the elderly and persons with underlying medical conditions. High-risk groups for severe disease include the elderly, children aged six months to four years, pregnant women regardless of trimester, immunosuppressed individuals or people with chronic medical conditions [34,35]. All EU/EEA countries have recommendations targeting older adults, as well as groups with underlying medical conditions [36]. Healthcare workers should be encouraged to receive vaccination against influenza to reduce the risk of infecting vulnerable groups, in addition to protecting themselves.

Influenza vaccination campaigns are underway in the EU/EEA and target groups should be encouraged to be vaccinated. To maximise uptake, similar approaches as for the promotion of COVID-19 vaccination should be applied. Several countries are running combined campaigns against COVID-19 and influenza, since this approach could be more efficient in terms of administration, logistics and cost. Data for seasonal influenza vaccine uptake will be available later in the season.

RSV

Two RSV vaccines (Abrysvo™ [37] and Arexvy™ [38]) for the prevention of disease in older adults and infants through maternal vaccination have been granted marketing authorisation for use in the EU/EEA. Assessment of evidence is ongoing or planned in EU/EEA countries for inclusion in routine vaccination programmes, following NITAG advice and cost-effectiveness analyses. To date, three countries [39-41] in the EU/EEA have issued recommendations for use of RSV vaccine in older adults (60+ or 75+ years of age according to national recommendations).

IPC measures and management of cases

Strengthening appropriate IPC practices mitigates the spread of respiratory viruses in both the community and healthcare facilities. During the current high community virus transmission period, it is advised that in addition to appropriate hand and respiratory hygiene, staff, visitors and patients in both primary and secondary healthcare settings wear medical face masks (universal masking) or FFP2 respirators in common areas of the hospital, patient rooms and other areas where patient care is provided.

Implementation of multi-layered interventions is the key to preventing strain on hospital personnel and other resources [42]. In healthcare facilities, the mainstay of IPC comprises a set of measures always used by healthcare workers including administrative measures (such as triage and placement of patients, in this case patients with respiratory symptoms), healthcare precautions (especially hand hygiene), appropriate use of personal protective equipment (PPE) by HCWs and environmental measures (such as cleaning and ventilation). Rapid tests for the early detection of COVID-19, influenza and RSV, and testing in general for viruses, facilitates both the management of patient admissions and appropriate room and bed allocation in accordance with IPC recommendations as well as their treatment. Ideally, patients with confirmed respiratory viral infection, or probable respiratory viral infection with confirmatory test results pending, should be placed in a single room. If the number of cases exceeds the single-room capacity, patients with the same viral infection can be placed in the same room (cohorting). Alternatively, healthcare workers in contact with patients should wear a medical face mask during all routine patient care (targeted clinical masking). Decisions on implementation of universal or targeted clinical masking should consider the expected benefit, as well as the burden on resources, staff, patients and visitors.

Healthcare facilities should ensure that PPE is available and appropriately used to safeguard staff providing patient care. A risk assessment should be conducted to support appropriate selection of PPE. It is recommended that healthcare workers interacting with patients who have viral respiratory infections, without close proximity or long exposure to the patient, should wear a medical face mask, as a minimum.

Clinicians should consider early diagnosis and treatment, when indicated, to prevent progression to severe disease. Antiviral drugs are available and approved in EU/EEA for the treatment of COVID-19 within five days from the onset of symptoms (nirmatrelvir/ritonavir (Paxlovid™), remdesivir and monoclonal antibodies) and influenza, preferably within 48hrs from the onset of symptoms (oseltamivir, zanamivir and baloxavir). Antibiotics can be used to treat respiratory infections caused by bacteria such as Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection or other bacteria, when patients present with prolonged or atypical, severe lower respiratory tract symptoms, and based on medical evaluation. Antibiotics are not effective against viruses and guidance for the prudent use of antibiotics should be included in awareness campaign(s). In 2022, nirsevimab, a recombinant human monoclonal antibody was authorised for EU/EEA countries as a one-off injection ahead of the RSV season [23] and indicated the prevention of RSV disease in neonates and infants. Some EU/EEA countries including France [43], Luxembourg [44] and Spain

[45] have issued recommendations for its use. For RSV, no prevention measure was available before, except palivizumab [46], a monoclonal antibody for the prevention of serious lower respiratory tract infections in high-risk groups.

The combination of increased hospital visits/admissions and high numbers of staff being infected with circulating viruses may exert enormous pressure on healthcare systems around Europe in the coming weeks. Maintaining an

adequate ratio of staff to patients, especially in adult and paediatric emergency departments and ICUs is critical for patient safety and quality of care. Appropriate measures to alleviate understaffing in critical units should be taken by prioritising and allocating resources effectively according to the foreseeable needs.

Risk communication

Generally, good hygiene practices in the community should be promoted, including targeted guidance for risk groups, healthcare workers and caretakers of vulnerable groups. Messaging should include vaccination promotion, staying home when ill; good hand and respiratory hygiene, appropriate ventilation of indoor spaces. The use of medical face mask (as a minimum) when in crowded public spaces can also be promoted, particularly for people at high risk for severe disease from circulating viruses, or people with respiratory symptoms who cannot stay home.

Reports from some countries indicate relatively low COVID-19 vaccine uptake in the 65+ age group (ranging between 20-73%) [29,30]. Regarding vaccination, it is important to understand the reasons for suboptimal levels of acceptance and uptake of both seasonal influenza and COVID-19 vaccines. Member States may consider using the ‘5Cs diagnostic model for vaccination’ to understand the factors that may be addressed through risk communication. The 5Cs stand for Confidence, Complacency, Constraints, Collective Responsibility and Calculation, all of which can be amenable to risk communication messaging. The 5Cs model is translated into all 24 official EU languages [47].

Five additional key areas may be considered in risk communication messages in the context of promoting vaccination uptake:

- Vaccines in use today have been updated to provide protection against currently circulating subtypes of SARS-CoV-2 and influenza viruses and are expected to protect against development of severe disease.

- At this stage, there is an overwhelming body of evidence in support of the safety and effectiveness of COVID- 19 and influenza vaccines.

- Every effort should be made to ensure that the messengers used in risk communication activities are known and trusted by the target populations.

- Messages should provide clear instructions regarding where and how people can be vaccinated.

- In countries where recommendations for the new RSV vaccine are introduced, extra efforts should be made to promote this vaccine for the identified risk groups.

Consulted ECDC experts (in alphabetical order)

Sabrina Bacci, Agoritsa Baka, Niklas Bergstrand, Jordi Borell-Pique, Eeva Broberg, Orlando Cenciarelli, Bruno Ciancio, Tarik Derrough, Luisa Hallmaier-Wacker, Ole Heuer, John Kinsman, Leah Martin, Angeliki Melidou, Aikaterini Mougkou, Dorothee Obach, Ajibola Omokanye, Giulia Perego, Elisabetta Pierini, Diamantis Plachouras, Gianfranco Spiteri, Maike Winters.

References

Share this page