Shigatoxin/verocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC/VTEC) infection - Annual Epidemiological Report 2016 [2014 data]

STEC VTEC-Annual Epidemiological Report 2016

English (142.14 KB - PDF)Key facts

- In 2014, 6 109 confirmed cases of infections with Shigatoxin/verocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC/VTEC) were reported in the EU/EEA.

- The EU/EEA notification rate was 1.4 cases per 100 000 population.

- The highest confirmed case rates were observed in 0–4-year-old children (7.6 cases per 100 000 population).

- The rate per 100 000 population increased during 2010–2013 in EU/EEA, but stabilised in 2014.

- The highest notification rates were reported in Ireland, Denmark, the Netherlands and Sweden.

Methods

Click here for a detailed description of the methods used to produce this annual report

In 2014, 29 EU/EEA countries reported data on STEC/VTEC infections. Eleven of the 29 countries used the latest case definition (EU 2012), 11 countries reported in accordance with the previous case definition (EU 2008), and seven countries reported using other definitions or did not specify which case definition was used.

The notification of STEC/VTEC infections is mandatory in most EU/EEA countries except for five Member States where notification is either voluntary (Belgium, France, Italy and Luxembourg) or based on another type of system (the United Kingdom). Portugal does not have a surveillance system for STEC/VTEC. The surveillance systems for STEC/VTEC infections have full national coverage in all EU/EEA countries except for Belgium, France and Italy. The majority of EU/EEA countries (24 of 29) have a passive surveillance system, and in 20 countries cases were reported by both laboratories and physicians and/or hospitals. Five countries have only laboratory-based reporting. In France, the STEC/VTEC surveillance is centred on paediatric haemolytic-uraemic syndrome (HUS) surveillance, and in Italy it is primarily based on the national registry of HUS. Twenty-eight EU/EEA countries reported case-based data, and one country reported aggregated data (Annex).

In addition to case-based TESSy surveillance, ECDC coordinates molecular typing-enhanced surveillance of STEC/VTEC through isolate-based data collection. A typing-based multi-country cluster of STEC/VTEC is currently defined as at least two different countries reporting at least one isolate each with matching XbaI pulsotypes, with the reports a maximum of eight weeks apart.

Epidemiology

In 2014, 6 167 cases of STEC/VTEC infections were reported by 29 EU/EEA countries. Of these cases, 6 109 were confirmed cases. Twenty-six countries reported at least one confirmed case, and three countries reported zero cases. The EU/EEA notification rate was 1.4 per 100 000 population, which is at the same level as in 2013.

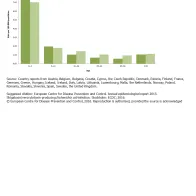

The highest country-specific notification rates were observed in Ireland, the Netherlands, Denmark and Sweden (12.4, 5.5, 5.0 and 4.9 cases per 100 000 population, respectively). For the period 2010–2014, the highest country-specific increases in notification rates were observed in Ireland (90%) and in the Netherlands (188%). The increases in these two countries could, to a large degree, be explained by a change in the laboratory methods used for diagnosis: laboratory analysis is now able to detect bacteria in asymptomatic carriers. Eleven countries (Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Greece, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, and Spain) reported ≤0.1 cases per 100 000 population (Table 1 and Figure 1).

Of 6 086 confirmed cases with known gender, 46.0% were male. The male-to-female ratio was 0.8:1 in 2014. The highest rate of confirmed cases was reported in the age group 0–4 years for both genders (7.6 cases per 100 000 population) and particularly in males (8.2 cases per 100 000 population). This is 4.0 to 9.5 times the notification rate reported in the older age groups (Figure 2).

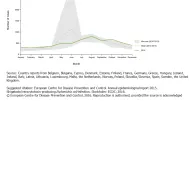

There was a clear seasonal trend in confirmed STEC/VTEC cases reported in the EU/EEA between 2010 and 2014, with more cases reported during the summer months (Figure 3).

The prominent peak of STEC/VTEC cases (Figure 4) in the summer of 2011 was due to the large STEC O104:H4 outbreak affecting more than 3 800 people in Germany alone, with additional cases in 15 other countries [1]. There was clear increase in the trend in 2012 compared with the situation before the outbreak in 2010, however the trend seemed to stabilise in 2012–2014.

Molecular typing − enhanced surveillance

In 2014, eight countries submitted STEC/VTEC typing data to TESSy. No multi-country clusters were detected.

Threats description for 2014

No STEC/VTEC-related threats were detected by event-based surveillance in 2014.

Discussion

In 2014, STEC/VTEC was the fourth most commonly reported zoonosis in the EU [2]. The EU/EEA notification rate for human STEC/VTEC infections increased from 2010 to 2013, but seemed to stabilise thereafter. In the summer of 2011, a large enteroaggregative Shiga toxin-producing E. coli (STEC) O104:H4 outbreak was associated with the consumption of contaminated raw sprouted fenugreek seeds. More than 3 800 persons in Germany were affected, with additional linked cases in 15 countries [1]. From 2007 to 2010, the reported EU/EEA notification was below 1.0 STEC/VTEC cases per 100 000 population. In 2012, however, one year after the outbreak, a 1.8-fold increase in the EU/EEA notification rate was observed compared with the years before the outbreak. Part of this increase can be explained by an increased general awareness with regard to STEC/VTEC, an increased use of PCR for the detection of VTEC in stool samples, and an increasing number of laboratories testing for serogroups other than O157 [3].

The STEC/VTEC serogroups most frequently found in food samples (O157, O26, O103, O113, O146, O91, O145) are those most commonly reported in human infections, with serotype O157 representing about half of the cases [2,4,5]. Most human cases are sporadic. In 2014, STEC/VTEC was reported as the causative agent in seven outbreaks with known food source, representing 1.2% of all the foodborne outbreaks reported at the EU level. Five of the outbreaks were caused by STEC/VTEC O157. Three of these outbreaks were associated with milk (two from unpasteurised milk), and two outbreaks were associated with different types of ready-to-eat salads [2].

Surveillance of STEC/VTEC infections is mandatory and covers the whole population in most EU/EEA countries. However, some countries have only laboratory-based reporting, and in two countries, surveillance is based only on reported cases of haemolytic-uraemic syndrome (HUS). A small proportion of STEC/VTEC patients – particularly children – may develop HUS, which is characterised by acute kidney failure and requires hospital care.

In 2014, the average proportion of hospitalised STEC/VTEC cases was relatively high (40%) [2]. The highest proportions of hospitalised cases were reported in a Member State with a HUS-focused surveillance system and in countries reporting the lowest notification rates, indicating that several countries – in addition to the two countries for which this is known – seem to focus on the surveillance of the most severe cases. The age group affected the most by STEC/VTEC were infants and children up to 4 years of age, who accounted for almost one-third of all confirmed cases in 2014. This was also seen in the HUS cases, where two thirds of the cases were reported in patients who were 0–4 years old [2].

Public health conclusions

The EU/EEA notification rate for human STEC/VTEC infections has increased after the large STEC/VTEC outbreak in 2011 compared with the situation before the outbreak. The majority of the Member States reported an increase in the notification rate in 2012 compared with the situation in 2010, with the highest country-specific increase in notification rates observed in Ireland and in the Netherlands. Part of this increase could be explained by increased awareness with regard to STEC/VTEC due to the 2011 outbreak; additional explanations are i) increased case detection through improved diagnostic methods and ii) the growing number of laboratories capable of identifying other serogroups than only the most common one, O157 [3]. No increase, however, was observed in the 11 countries which before the outbreak reported the lowest notification rates and the highest hospitalisation rates, which implies that these countries did also not experience an increase in severe STEC/VTEC infections. After the 2011 outbreak, the EU/EEA trend stabilised at the same high level as before the outbreak.

As STEC/VTEC infection is mainly acquired by contact with animals and/or their faeces and by consuming contaminated food, good hygiene practices in premises dealing with animals and food processing can decrease the risk of infection. In 2014, no STEC/VTEC-positive samples were reported for sprouted seeds, the sole food category for which microbiological criteria for STEC/VTEC have been established in the EU after the 2011 outbreak [2]. Adequate cooking of food, particularly beef, and the use of pasteurised milk further reduce the risk of foodborne STEC/VTEC infections.

References

- European Food Safety Authority and European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. The European Union summary report on trends and sources of zoonoses, zoonotic agents and food-borne outbreaks in 2011. 2013;11(4):3129.

- European Food Safety Authority and European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. The European Union summary report on trends and sources of zoonoses, zoonotic agents and food-borne outbreaks in 2013. EFSA Journal 2015; 13(1):3991.

- European Food Safety Authority and European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. The European Union summary report on trends and sources of zoonoses, zoonotic agents and food-borne outbreaks in 2014. EFSA Journal 2015; 13(12):4329.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Surveillance of seven priority food- and waterborne diseases in the EU/EEA 2010−2012. Stockholm: ECDC; 2015.

- EFSA BIOHAZ Panel (EFSA Panel on Biological Hazards). Scientific opinion on VTEC-seropathotype and scientific criteria regarding pathogenicity assessment. EFSA Journal 2013;11(4):3138.

Reported confirmed VTEC infection cases: number and rate per 100 000 population, EU/EEA, 2010–2014

Reported confirmed STEC/VTEC infection cases: rate per 100 000 population, EU/EEA, 2014

Figure 2. Reported confirmed STEC/VTEC infection cases: rates by age groups and gender, EU/EEA, 2014

Reported confirmed STEC/VTEC infection cases: rates by age groups and gender, EU/EEA, 2014

Reported confirmed STEC/VTEC infection cases by month, EU/EEA, 2014 compared with 2010−2013

Reported confirmed STEC/VTEC infection cases: trend and case numbers, EU/EEA, 2010−2014

Share this page