Evidence-based advice processes for long-term care facilities in the COVID-19 pandemic - Report from the after-action review (AAR) in Norway

Executive Summary

The Omicron variant wave initially led to a renewed sense of scientific uncertainty and general anxiety in Norway. However, as new evidence emerged suggesting that the new variant was not only highly transmissible but also caused less severe clinical disease, these concerns were replaced with more lenient recommendations for the LTCFs and society in general. The purpose of this AAR is to shed light on the advicemaking process underlying these decisions. How was evidence used to inform advice for LTCFs during the initial Omicron period?

The focused AAR’s core methodology is a process-driven learning exercise that builds on a qualitative review of a delimitated situation, in this case the advice-making process for LTCFs during the emergence of Omicron VOC. The case study approach allows for in-depth explorations of how key advice is produced across relevant organisations as well as how it changes over time considering new evidence. This involves identifying and making explicit any external pressures, informal practices, and networks (both within and across agencies) that affect the advice making

process. Data gathering consisted of a two-day consultation with key stakeholders (identified by the Norwegian Institute of Public Health (NIPH)) together with semi-structured interviews.

The advice-making process in Norway was influenced by international evidence (primarily from Denmark and Public Health Scotland), experience-based evidence from the doctors and leaders of the LTCFs, and, most importantly, the availability of daily epidemiological data across all Norwegian municipalities. NIPH and the Norwegian Directorate of Health (NDH) were also able to draw on many other types of relevant evidence and practices, allowing them to make the necessary evidence-informed changes to their advice: international evidence, peer-reviewed evidence,

multidisciplinary practices, communication inputs upstream and experience-based evidence from LTCFs and the municipal authorities. The staff from the health agencies would have liked to include more strongly the voice of the LTCF residents and family members and behavioural science in the advice-making process.

The NIPH relied on a layered advice system where they would provide context-specific guidance. The municipalities had the flexibility to reflect on the proportionality of the advice, thus taking active part in the advice-making process. The advice-making process with regards to LTCFs appears not to have been subject to much pressure from the media or public opinion. However, freedom of information requests as well as Ministry of Health assignments in general strained the resources in both agencies.

An effective advice-making process during Omicron was made possible by:

- the availability of relevant epidemiological data disaggregated to the level of LTCF, allowing for quite robust inferences with regards to the implications of the Omicron wave;

- strong existing procedures and channels for exchanging information and advice down the system from the health agencies to the municipal authorities, and finally to the LTCFs;

- a high level of trust in the advice given by the NIPH and NDH among LTCF leaders and staff; and

- a high implementing capacity in the LTCFs, which is both the result of having highly qualified staff and adequate resources and of an updated and resilient preparedness system at the local level (with a digital monitoring system in place in many municipalities).

Procedures and guidelines were in place and had in many cases been stress-tested in practice during the previous wave of the pandemic. There are several good practices to learn from the Norwegian experience with LTCF advice during Omicron, some of which were implemented while others were only highlighted in the discussions:

- the importance of maintaining trust-based relationship down the advice-making chain to the municipal authorities and LTCFs (maintained through webinars, online meetings, formal reference groups and a 24/7 telephone hotline for staff);

- the need for concentrating data and information to a few online outlets/platforms to allow easy access and avoid conflicting advice;

- the importance of having updated national action plans and practices that have been integrated into the institution and incorporated into daily routines during peacetime;

- the need for clearly defined responsibilities and divisions of labour between the two health agencies (NIPH and NDH);

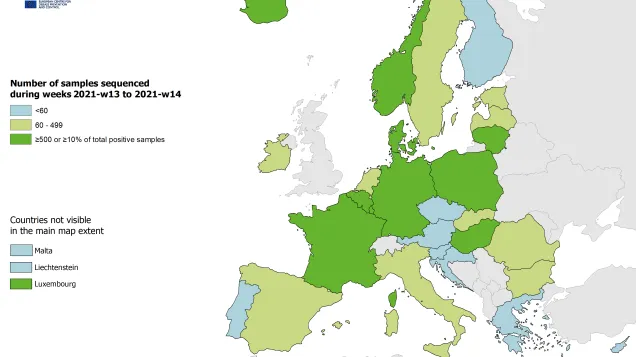

- the advantage of digitalisation and standardisation of epidemiological data to allow for daily updates on a disaggregated level that can be integrated into the advice-making process.

Further, the workshop emphasised the need for retaining adequate preparedness and response functions going forward and cautioned against retrenching staff and expenses in a post-pandemic phase. Effective procedures, collaborations, know-how, interdisciplinary workings, and learnings that have been built and refined during the years of pandemic crisis need to be retained within the institution, so that the knowledge is not lost when staff members leave their current positions. An important lesson learned is that it is very difficult to dial the pandemic preparedness capacity up and down quickly according to short-term needs. Effective pandemic preparedness and response, therefore, demands long-term investments that include continued training, updating of pandemic plans, surveillance, and conducting interdisciplinary evaluations of both crisis management processes and interventions to prepare for future health crises.

After Action Review of LTCFs during COVID19 in Norway

English (1.94 MB - PDF)