Factsheet for health professionals about hepatitis C

Disclaimer: The information contained in this factsheet is intended for general information and should not substitute individual expert advice or judgement of healthcare professionals.

Hepatitis C is a liver disease caused by infection with the hepatitis C virus (HCV). HCV can cause both acute and chronic hepatitis infection, ranging in severity from a mild illness that lasts only a few weeks to a serious, lifelong illness resulting in cirrhosis and liver cancer.

Case definition

Hepatitis C is notifiable in the European Union (EU). The case definition has been developed for surveillance purposes. European Union/European Economic Area (EU/EEA) countries report data on newly diagnosed cases of hepatitis C to the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) on an annual basis in accordance with the EU 2018 case definition and differentiate between acute and chronic infections using defined criteria (Table 1) [1]. When it is not possible to use the EU 2018 case definition, other national case definitions are also accepted [1-3].

The European case definition is as follows:

HEPATITIS C*

Clinical criteria:

Not relevant for surveillance purposes.

Laboratory criteria:

At least one of the following three:

- Detection of hepatitis C virus nucleic acid (HCV RNA)

- Detection of hepatitis C virus core antigen (HCV-core)

- Hepatitis C virus specific antibody (anti-HCV) response confirmed by a confirmatory (for example, immunoblot) antibody test in persons older than 18 months without evidence of resolved infection.)

* When reporting cases of hepatitis C, the Member States should distinguish between acute and chronic disease, according to ECDC requirements.

Table 1. Case definition of acute and chronic hepatitis C virus infection for reporting purposes

|

Stage |

Definition |

|---|---|

| Acute |

or

|

| Chronic | Detection of hepatitis C virus nucleic acid (HCV RNA) or hepatitis C core antigen (HCV-core) in serum/plasma in two samples taken at least 12 months apart* |

| Unknown | Any newly diagnosed case which cannot be classified in accordance with the above description of acute or chronic infection. |

*in the event that the case was not notified the first time.

The pathogen

Hepatitis C is a liver infection caused by the hepatitis C virus (HCV) [4-6]. Infection with HCV can cause both acute (short-term) and chronic (long-term) disease that can damage the liver. The virus belongs to the Flaviviridae family (new ICTV nomenclature: species Hepacivirus hominis [7]) and is a small, enveloped, positive-sense single stranded RNA virus. The high replication rate and short half-life of the viral RNA leads to a high sequence diversity (quasispecies) within the host due to the error rate of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase [8].

HCV is classified into seven major genotypes and 67 subtypes are described [9,10]. Some genotypes are associated with higher disease severity [11].

In Europe, genotype 1 (1b > 1a) is the most frequent viral HCV genotype followed by genotypes 3 and 2, while genotype 4 is more prevalent in Central Africa and the middle East and genotype 3 on the Indian subcontinent [12].

Clinical features and sequelae

Initial infection with HCV causes an acute short-term and mostly asymptomatic infection. The incubation period is around 2−12 weeks, and clinical symptoms can appear from two weeks to six months afterwards [11,13].

Between 15−25% of people with acute HCV infection are able to clear the virus spontaneously. In rare cases, an acute hepatitis infection can be severe, with a fulminant clinical course resulting in liver failure and death.

Clinical symptoms of acute infections are similar to other viral hepatitis infections:

-

Icterus/jaundice (yellowing of the skin and eyes)

-

Nausea and vomiting

-

Dark urine

-

Abdominal pain

-

Fatigue.

The majority of infected individuals do not clear the virus during the acute phase and develop chronic hepatitis C, where the virus persists in the liver. Chronic hepatitis C is defined by the presence of viral RNA or antigen indicating active replication for at least six months. Chronic hepatitis C virus infection can lead to the development of severe liver damage, such as cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), that may require liver transplantation or lead to liver-related death from the disease if not treated. The time span from infection to severe complications, or even fatal outcome, can be between 20 and 60 years. Around 20% of patients with untreated chronic HCV develop cirrhosis within 20 years and a lower proportion of patients will develop liver cancer after 20−40 years. Chronic HCV can lead to liver failure which requires liver transplantation. Co-factors such as alcohol consumption, age, level of liver inflammation and fibrosis, other infections such as hepatitis B or D virus, or HIV infection play a role in the disease progression [11].

Extrahepatic manifestations may include cryoglobulinemia, vasculitis, lymphoma, cardiomyopathy, insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes [14,15].

The infection with one genotype does not provide neutralising immunity against other genotypes and co-infections with different HCV geno- or subtypes are observed, particularly in high-risk groups.

Reinfection can occur in patients who have cleared the virus or acquired treatment-induced sustained virological response (SVR) after 12 or 24 weeks post-SVR. Identification of a different genotype or viral strain, together with previous diagnosis of SVR, confirm reinfection.

Epidemiology

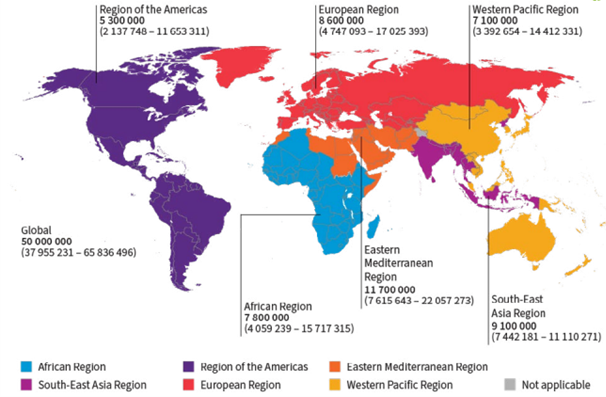

Hepatitis C is one of the main causes of viral hepatitis and chronic liver disease, representing a major public health threat globally. In 2024, an estimated 50 million people were living with HCV infection with an incidence of one million new cases per year, and 240 000 attributable deaths in 2022 (Figure 1) [5,6,16-19]. The disease burden is also high in the World Health Organization (WHO) European Region where an estimated 12 million (1.6%) people are chronically infected. The prevalence in the European Union and European Economic Area (EU/EEA) is lower, with an estimated 1.8 million people living with chronic hepatitis C (0.5%) (Figure 2) [20]. According to WHO, in the WHO European Region each year more than 20 000 people die due to hepatitis C [20].

Virus genotypes have different distributions globally and these can be used for molecular epidemiological analyses, including the identification of HCV reinfection [12].

Figure 1. Global distribution of chronic hepatitis C virus infections by WHO Region, 2022

from the WHO Global hepatitis report 2024: action for access in low- and middle-income countries [21]

Figure 2. Prevalence of hepatitis C in the EU/EEU 2024 [22]

Transmission

HCV is predominantly transmitted through blood (blood-borne virus) but may also be present in other bodily fluids. The most common mode of transmission is via the use of contaminated needles (shared needles, tattooing equipment or other) or medical equipment (needle stick injuries, hygiene or sterilisation breaches in nosocomial intra-healthcare settings) and contaminated blood transfusions or blood products (e.g. haemodialysis). The risk of sexual or vertical transmission through unsafe sex with an infected person or vertically from a mother to her child during the pregnancy or delivery is lower than through blood-to-blood contact [4,6].

In EU/EEA countries, reported routes of transmission are injecting drug use, nosocomial infection and sex between men as well as non-occupational injuries [23].

Diagnostics

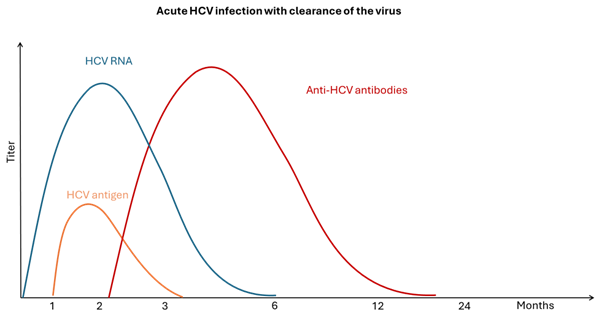

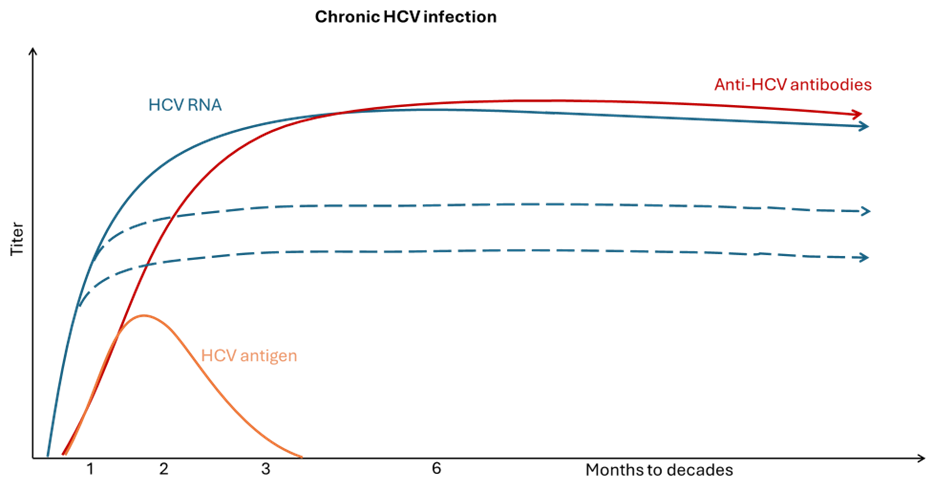

The clinical symptoms of viral hepatitis caused by different viruses are not discriminatory and it is not possible to distinguish between pathogens, which is why laboratory diagnosis is required to confirm hepatitis C virus infection. Different virological and serological markers of infection have been identified to assess the status of either an acute or chronic infection (Table 2). In addition, clinical measures, such as ultrasound, fibroscan or biopsy, analyse the level of fibrosis and monitor the progression of the liver disease. The markers of infection and clinical parameters are also important for treatment monitoring (Figures 3-4). WHO has also produced guidance to aid with diagnostics which is available on its website: WHO Guidelines on hepatitis B and C testing [24].

The virological diagnosis of HCV infection is based on two categories of laboratory tests: serological assays detecting specific antibodies to HCV (anti-HCV) (indirect tests) and assays that can detect the components of HCV viral particles, such as HCV RNA and core antigen (direct tests).

Anti-HCV antibodies (Anti-HCV) (antibodies against HCV antigens)

Anti-HCV tests are the primary tests used to determine exposure to HCV infection and typically involve a serum or plasma sample. Anti-HCV point-of-care tests are also available using whole blood from a capillary fingerstick sample. Although antibodies persist on a lifelong basis, they can wane after viral clearance or treatment-induced SVR. The antibody seroconversion window period for HCV infection varies from an average of eight weeks up to 12 weeks so anti-HCV will not be detectable in the very early phase of an acute infection. Anti-HCV may also not be detectable in immunosuppressed patients with chronic hepatitis C. If an initial HCV antibody test is positive (indicating past or present infection), a reflex test will be performed to detect viral HCV RNA in the blood to confirm an active infection.

HCV RNA: Hepatitis C virus genome

Molecular virological techniques play a key role in diagnosis and monitoring response to treatment for HCV. HCV RNA testing is critical for confirming current infection. Current HCV infection is generally determined in the laboratory through a qualitative or quantitative HCV RNA test using serum or plasma collected from whole blood. Nucleic acid testing using PCR to detect HCV RNA is considered the ‘gold standard’ for detecting active HCV replication. HCV RNA will be negative in the case of past infection with clearance (either from a spontaneously resolved infection or if cured from antiviral treatment) but may also be negative in the very early period post-exposure.

HCV core antigen (HCVcAg): Hepatitis C core antigen

The detection of the core antigen of HCV by immunoassay approaches was developed as an alternative to nucleic acid amplification technology to be used in resource-limited settings, where molecular laboratory services are either not available, or not widely used owing to cost. The detection of core antigen indicates viraemia in patients and is a marker for viral replication. The tests have a lower sensitivity compared to HCV RNA detection, but newer tests show comparable sensitivities.

Figure 3. Acute HCV infection with clearance of the virus

Adapted from WHO Guidelines on hepatitis B and C testing [24]

Figure 4. Chronic HCV infection with persistence of the virus

Adapted from WHO Guidelines on hepatitis B and C testing [24]

Table 2. Markers for the discrimination of acute and chronic HCV infection

| Marker | Acute | Chronic |

| Anti-HCV core antibody | Negative | Positive |

| HCV RNA | Positive | Positive (fluctuating levels) |

| HCV core antigen | Positive | Positive |

The following specimens are best suited to test for the different HCV markers:

Serum/plasma

- All HCV antigens

- All antibodies to HCV

- HCV RNA

- HCV sequence information.

Oral fluid (not saliva)

- Anti-HCV antibodies.

Finger prick blood

- Anti-HCV antibodies

- (HCV RNA).

Dried blood spots

- Anti-HCV antibodies

- HCV RNA.

Case management and treatment

Warning: this chapter should not be intended as clinical advice. Specific clinical guidelines are provided by The European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) and can be consulted here: Hepatitis C Archives - EASL-The Home of Hepatology.

Different direct-acting antiviral agents (DAAs) are available for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C. DAA therapies are highly effective and have SVR rates of over 95% after eight to 24 weeks of treatment in most patients [25]. EU-authorised drugs for HCV treatment include the following:

Pangenotypic drugs or drug combinations

-

Sofosbuvir (Sovaldi) [26]

-

Sofosbuvir Velpatasvir (Epclusa) [27]

-

Sofosbuvir Velpatasvir Voxilaprevir (Vosevi) [28]

-

Glecaprevir/pibrentasvir (Maviret) [29].

Genotype-specific drugs or drug combinations

-

Ledipasvir/sofosbuvir (Harvoni) [30]

-

Grazoprevir/elbasvir (Zepatier) [31].

Treatment courses last between three and six months. Treatment is aimed at curing chronic hepatitis C, eliminating the virus from the body and reducing liver damage. Successful treatment can even reduce the severity of fibrosis and cirrhosis. The goal is sustained virological response (SVR) which is characterised by undetectable HCV RNA in serum or plasma 12 weeks (SVR12) or 24 weeks (SVR24) after the completion of the antiviral treatment. A very low chance of late relapse is observed when HCV is cured with SVR.

Non-cirrhotic patients can achieve normalisation of the liver enzymes and inflammation following SVR. After SVR, patients with cirrhosis and fibrosis have continued but lower risk of complications, such as liver failure, compared to untreated patients with chronic hepatitis C. Treatment of hepatitis-C-virus-infected patients reduces the all-cause mortality.

Resistance to antiviral treatment (e.g. NS5A, NS5B or NS4A inhibitors) can occur and some genotypes or subtypes may be more resistant to treatment or show different response rates, requiring different doses or treatment durations −e.g. genotype 3 [25]. If possible, viruses should be sequenced in patients among whom the likely place of infection was in areas where those geno- or subtypes are prevalent.

For further details on treatment recommendations, please consult the publication of The European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) EASL recommendations on treatment of hepatitis C: Final update of the series from 2020 [32].

Public health prevention and control measures

No vaccine exists for hepatitis C but there are effective prevention measures that can reduce the risk of hepatitis C transmission, including harm reduction measures for people who inject drugs, safe sexual practices and strict infection prevention and control measures in healthcare settings.

Injecting drug use remains an important risk factor for acquiring blood-borne and other infectious diseases such as HCV. ECDC and the European Union Drugs Agency (EUDA) have jointly published guidance Prevention and control of infectious diseases among people who inject drugs - 2023 update providing an evidence base for countries to develop national strategies, policies, and programmes to prevent and control infections and infectious diseases among people who inject drugs [33]. The guidance also outlines how to monitor and evaluate prevention and control strategies, policies, and programmes related to people who inject drugs.

Early diagnosis and treatment are the most important components to eliminate hepatitis C virus infection. Antiviral treatment with DAAs is an effective measure to cure hepatitis C and prevent further transmission. For further details see the EASL publication [32].

Hepatitis C virus infection can be prevented by:

- safe sex using condoms and reducing the number of sexual partners;

- harm reduction measures for people who inject drugs, including safe injection practices and the use of opioid agonist therapy for opiate users;

- using sterile needles and equipment during any invasive procedure including, piercing, or tattooing;

- strict enforcement of infection prevention and control measures in healthcare settings;

- blood safety strategies including the testing of substances of human origin − e.g. blood donations.

Elimination target for HCV

HCV is included in the WHO Regional action plans for ending AIDS and the epidemics of viral hepatitis and sexually transmitted infections 2022–2030 with an elimination target [20]. By 2030, a 90% reduction in number of new chronic hepatitis C infections and a 65% reduction in number of deaths should be achieved (Table 3) [20].

Table 3. Selected areas included in the 2025 interim and 2030 elimination target [20]

| Target areas (selected) | 2025 interim | 2030 target |

| Diagnosis of HCV | 60% | 90% |

| Treatment and cure of HCV | 50% eligible treated | 80% eligible treated |

| Blood donation screening | 100% | 100% |

| Distribution of sterile needle/syringe per person for people who inject drugs per year | 200 | 300 |

Advice to travellers

Disclaimer: Travel health physicians and travellers should always first consult national travel guidelines and recommendations as the primary source of information.

The distribution of hepatitis C varies across the globe, with some areas of high prevalence. Safe sex should be practised with new or different sex partners during trips abroad. People injecting drugs, or considering getting a piercing or tattoo should be aware of a possible increased risk of transmission related to HCV through shared needles or equipment in countries with high prevalence or where there may be suboptimal hygiene standards.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Introduction to the Annual Epidemiological Report. In: ECDC. Annual epidemiological report. Stockholm: ECDC; 2022 [cited 10 Jan 2024]. Available from: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/...

- European Commission (EC)... (2012/506/EU) – Annex 2.17 Hepatitis B (Hepatitis B virus) Brussels: European Commission; 2012 [cited 7 Feb 2024]. Available from: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/...

- European Commission (EC)... 2018 [cited 10 Jan 2024]. Available from: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/...

- Hofstraat SHI, Falla AM... Epidemiol Infect. 2017 Oct;145(14):2873-85.

- World Health Organization (WHO)... 2022 [cited 3 March 2024]. Available from: https://www.who.int/docs/...

- World Health Organization (WHO)... 2023 [cited 6 March 2024]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/...

- International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses... 2024. Available from: https://ictv.global/taxonomy/...

- Susser S, Vermehren J... J Clin Virol. 2011 Dec;52(4):321-7

- Simmonds P. Variability of hepatitis C virus. Hepatology. 1995 Feb;21(2):570-83

- Smith DB, Bukh J... Hepatology. 2014 Jan;59(1):318-27

- Chen SL, Morgan TR... Int J Med Sci. 2006;3(2):47-52

- Blach S, Zeuzem S... The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2017;2(3):161-76

- US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)... 2025 [23/06/2025]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis-c/...

- Zignego AL, Ferri C... Digestive and Liver Disease. 2007;39(1):2-17

- Cacoub P, Saadoun D... N Engl J Med. 2021 Jul 1;385(1):95-6

- World Health Organization (WHO)... Geneva: WHO; 2021 [cited 10 Jan 2024]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/...

- World Health Organization (WHO)... Geneva: WHO; 2016. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/...

- Polaris Observatory HCV Collaborators... Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 May;7(5):396-415

- Thomadakis C, Gountas I... Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2024 Jan;36:100792

- World Health Organization (WHO)... Copenhagen: WHO, 2023. Available from: https://www.who.int/europe/...

- World Health Organization (WHO)... WHO; 9 April 2024. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/...

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC)... Stockholm: ECDC, 2024. Available from: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/...

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC)... Stockholm: ECDC; 2025. Available from: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/...

- Falade-Nwulia O, Suarez-Cuervo C... Ann Intern Med. 2017 May 2;166(9):637-48

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). Sovaldi - Sofosbuvir 2014. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/...

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). Epclusa - sofosbuvir/velpatasvir 2016. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/...

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). Vosevi - sofosbuvir/velpatasvir/voxilaprevir 2017. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/...

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). Maviret - glecaprevir/pibrentasvir 2017. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/...

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). Harvoni - ledispavir/sofobuvir 2014. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/...

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). Zepatier - elbasvir/grazoprevir 2016. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/...

- Pawlotsky JM, Negro F... Journal of Hepatology. 2020;73(5):1170-218

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC), European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA)... Stockholm: ECDC; 2023. Available from: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/...

Related content

EU case definitions

Case definitions for each infectious disease covered by EU surveillance, as published in the Official Journal of the European Union.

Infographic

World Hepatitis Day 2016

This infographic explains the different types of hepatitis and explains what has to be done to eliminate viral hepatits as a public health threat in Europe