Disease information on hepatitis B

Disclaimer: The information contained in this factsheet is intended for general information and should not substitute individual expert advice or judgement of healthcare professionals.

Hepatitis B is a liver disease that results from infection with the hepatitis B virus (HBV) and is spread through contact with infected body fluids or blood products. Following acute infection with HBV, some people go on to develop a chronic infection.

Case definition

Hepatitis B is notifiable in the European Union (EU). The case definition has been developed for surveillance purposes. European Union/European Economic Area (EU/EEA) countries report data on newly diagnosed cases of hepatitis B to the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) according to the EU 2018 case definition on an annual basis and differentiate between acute and chronic cases using defined criteria (Table 1) [1]. If it is not possible to use the EU 2018 case definition, other national case definitions are accepted [1-3].

The European case definition is available here: EU case definitions and is as follows:

HEPATITIS B*

Clinical criteria:

Not relevant for surveillance purposes

Laboratory criteria:

Positive results for at least one or more of the following tests or combination of tests:

- IgM hepatitis B core antibody (anti-HBc IgM)

- Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg)

- Hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg)

- Hepatitis B nucleic acid (HBV-DNA).

* When reporting cases of hepatitis B, the Member States should distinguish between acute and chronic disease, according to ECDC requirements.

Table 1. Case definitions for acute and chronic hepatitis B for reporting purposes

| Stage | Definition |

|---|---|

| Acute |

Any of the below, with or without symptoms and signs (e.g. jaundice, elevated serum aminotransferase levels, fatigue, abdominal pain, loss of appetite, intermittent nausea, vomiting, fever):

or

|

| Chronic |

and

or

|

| Unknown |

|

a In the event that the case was not notified the first time.

The pathogen

Hepatitis B is a liver infection caused by the hepatitis B virus (HBV) (new taxonomy: Orthohepadnavirus hominoidei), a enveloped, hepatotropic DNA virus of the Hepadnaviridae family which replicates in hepatocytes and can integrate in the host genome [4,5].

HBV can be divided in 10 genotypes (A-J) based on their genome homology [6]. The most common genotypes are A–D. Genotypes vary in their global distribution and there are indications that some are associated with a different disease progression, clinical outcome in chronic infections, response to treatment or HBeAg seroconversion rates [6]. The viral genotypes have different distributions globally. Virus characterisation and molecular epidemiology can provide information to better understand routes of transmission and introduction into the EU from other regions.

HBV infection can cause both acute and chronic disease and may lead to the development of complications, including cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma.

HBV can remain infectious in the environment (e.g. on contaminated surfaces) for up to seven days. The incubation period is between 30−180 days, with most acute cases being recognised 30−60 days after infection [7].

Clinical features and sequelae

Acute infection with HBV commonly causes a short-term, often asymptomatic infection. Most healthy adults clear the virus within six months. Acute infections do not cause symptoms in 30−50% of adults and 90% of infants. Acute infections are usually self-limiting and result in temporary liver inflammation. In some cases, an acute hepatitis infection can be severe, with a fulminant clinical course resulting in liver failure. The overall case fatality associated with acute hepatitis B infection is 0.5−1% [7].

Clinical symptoms of acute infections are similar to other viral hepatitis infections:

- Icterus/jaundice (yellowing of the skin and eyes)

- Nausea and vomiting

- Dark urine

- Abdominal pain

- Fatigue.

HBV infection in adults is mostly an acute disease, and the virus is cleared by the immune system, with less than 5% of adults developing chronic disease. However, up to 90% of children infected before the age of five will develop life-long chronic HBV infection (see ‘Transmission’ section below). Chronic infection can lead to severe liver damage, including cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (liver cancer) which may result in death [4,8-12]. Within 10 years, 20−30% of patients with chronic HBV infection develop liver cirrhosis and each year, 2−4% of the patients with cirrhosis develop hepatocellular carcinoma, as do between 0.5−1% of those without cirrhosis (Table 2).

Table 2. Risk of progression by age at infection

| Indicator | Perinatal | Childhood | Adult |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion of infections leading to chronic infection | 80−90% | 30% | <5% |

| Proportion of patients with untreated HBV developing advanced liver disease | 20−30% | 5−10% | 1−2% |

| Phase with HBeAg positive chronic HBV infection | Prolonged | Variable | Short |

Modified from Natural history of hepatitis B virus infection - B Positive [13]

Chronic hepatitis B is a long-term infection with a persistence of the virus for more than six months which can lead to cirrhosis, liver failure and cancer (Table 3). Chronic HBV infections are associated with impairment of HBV-specific T-cell function and progress through phases. Most people with chronic HBV infection have no symptoms, but some may feel tired or have mild symptoms of an ‘acute hepatitis’ (see above).

In addition to acute and chronic infection, infection with HBV may result in occult HBV infection. This is a condition characterised by virus presence in the liver without having detectable virus markers in the blood. This means that an HBsAg-negative phase in serum with persistent viral DNA is not detectable in the blood. A reactivation of hepatitis B with HBsAg-negative status has been observed in patients following immunosuppression.

Hepatitis D virus (HDV) is a virus that is dependent on HBV replication and in 70−90% of the cases HBV/HDV co-infection leads to chronic clinical courses.

Table 3. Phases in chronic hepatitis B virus infections

| Marker | Phase 1 | Phase 2 | Phase 3 | Phase 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HBsAg | High | High/intermediate | Low | Intermediate |

| HBeAg | Positive | Positive | Negative | Negative |

| HBV DNA | > 107 IU/mL | 104 - 107 IU/mL | < 2000 IU/mL* | > 2000 IU/mL |

| ALT | Normal | Elevated | Normal | Elevated* |

| Liver disease | None/minimal | Moderate/severe | None | Moderate/severe |

| Terminology | HBeAg-positive chronic HBV infection | HBeAg-positive chronic HBV hepatitis | HBeAg-negative chronic HBV infection | HBeAg-negative chronic HBV hepatitis |

Adopted from EASL 2017 Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of hepatitis B virus infection [14];

* Can vary

Epidemiology

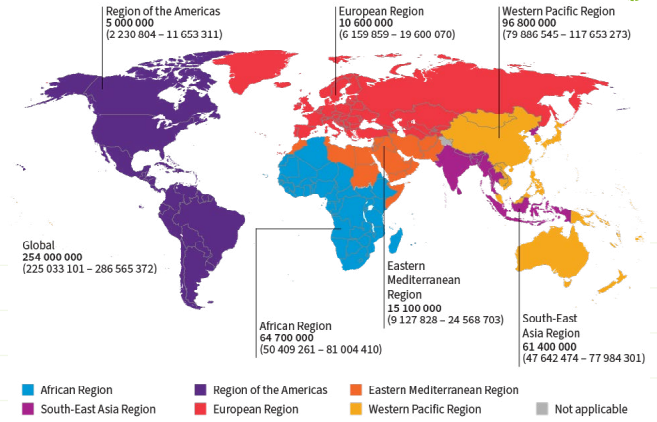

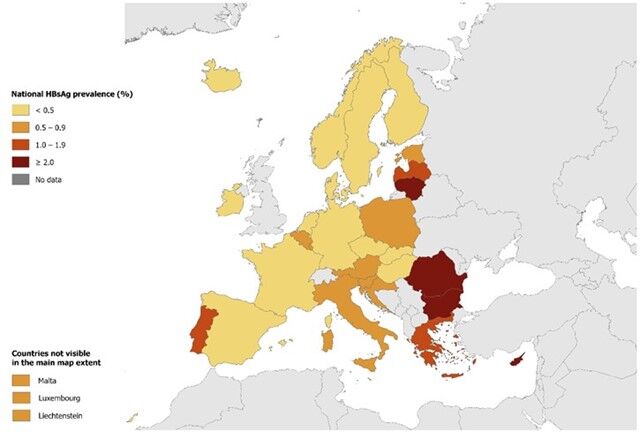

Viral hepatitis, caused by infection with HBV or hepatitis C virus (HCV), is a leading cause of death worldwide [15]. Cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma are sequelae of chronic HBV (CHB) infections which, together with hepatitis C virus (HCV) infections, account for the high disease burden associated with viral hepatitis. In a World Health Organization (WHO) report from 2024, the global prevalence for 2022 was estimated at 254 million people living with HBV infection, with an estimated incidence of 1.5 million new cases per year (Figure 1) [4,12,16]. For 2022, 1.1 million hepatitis B-associated deaths are estimated to have occurred globally, accounting for 83% of all viral hepatitis deaths [4,10,12]. Hepatitis B is also a major public health threat in the European Union/European Economic Area (EU/EEA) [10]. HBV prevalence data collected between 2018−2021 estimated that 3.2 million people are living with CHB in the EU/EEA (Figure 2) [17-19].

Figure 1. Global distribution of chronic hepatitis B virus infections by WHO Region, 2022

From the WHO Global hepatitis report 2024: action for access in low- and middle-income countries [12])

Figure 2. Prevalence of hepatitis B in the EU/EEU 2024 [20,21]

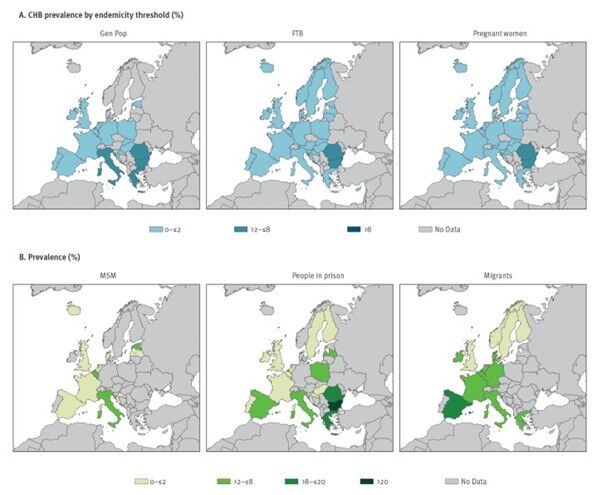

During the period 2005−2021, people who had migrated from endemic countries with higher HBV prevalence (median prevalence 5.8% [IQR 2.5−9.9]), together with people in prison (median prevalence 2.1 [1.9–3.7]) and men who had sex with men (median prevalence 0.7% [0.4–2.6]) were the groups with the highest HBV prevalence in the EU/EEA and the UK (Figure 3) [18]. Other at-risk populations include people who inject drugs and sex workers. Healthcare personnel are also among the groups at greater risk of being exposed to infected patients and contaminated medical equipment.

Figure 3. Weighted average prevalence estimates in different population groups, by country, EU/EEA/UK, 2005–2021 (n = 486) [18]

CHB: chronic hepatitis B; EEA: European Economic Area; EU: European Union; FTB: first-time blood donors; GenPop: general population; MSM: men who have sex with men; UK: United Kingdom.

Transmission

The virus is present in blood and other bodily fluids such as saliva, vaginal or menstrual fluids or semen. The most commonly reported route of transmission in Europe is through sexual transmission, when someone has sex without a condom with a person who has an HBV infection. Transmission is also reported through the sharing of needles and syringes, or other sharp objects that have been contaminated with blood or other body fluids from someone who has HBV. Transmission through contaminated objects may occur in healthcare settings, where appropriate precautions have not been taken, or in the community through accidental needlestick injury or, more commonly, injecting drug use. Transmission of infection is also possible through the transfusion of unscreened blood or blood products, but this is now extremely rare in Europe due the tight regulations in place. In countries where HBV is more widespread, the virus is more commonly transmitted from a mother with HBV to her baby at the time of birth (perinatal transmission) or during the first five years of life through exposure to infected blood in the household. Without intervention, the risk that HBV is transmitted from a mother to her child ranges from 70−90% for mothers who are HBeAg-positive or have a high HBV viral load to 10−40% for those who are HBeAg-negative. With intervention (antiviral treatment of the mother, immunoglobulin administration and vaccination of the newborn) the risk can be reduced to less than 10% [22].

Diagnostics

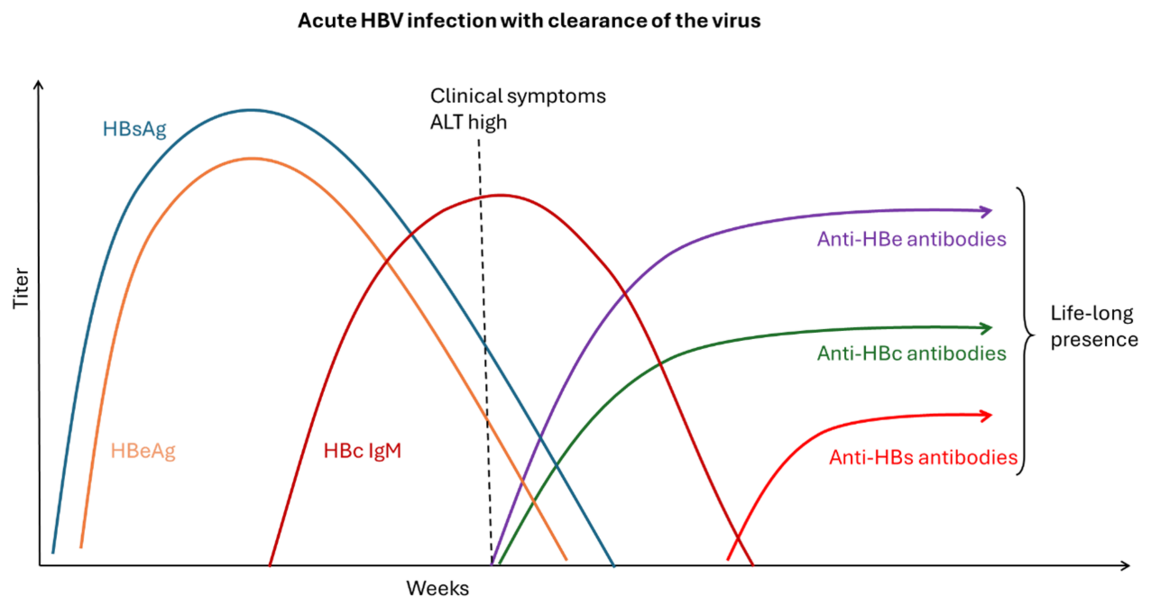

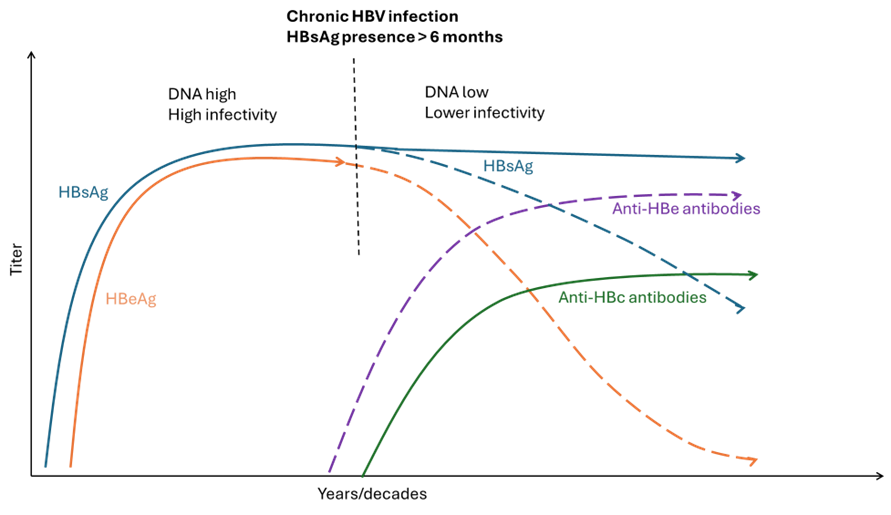

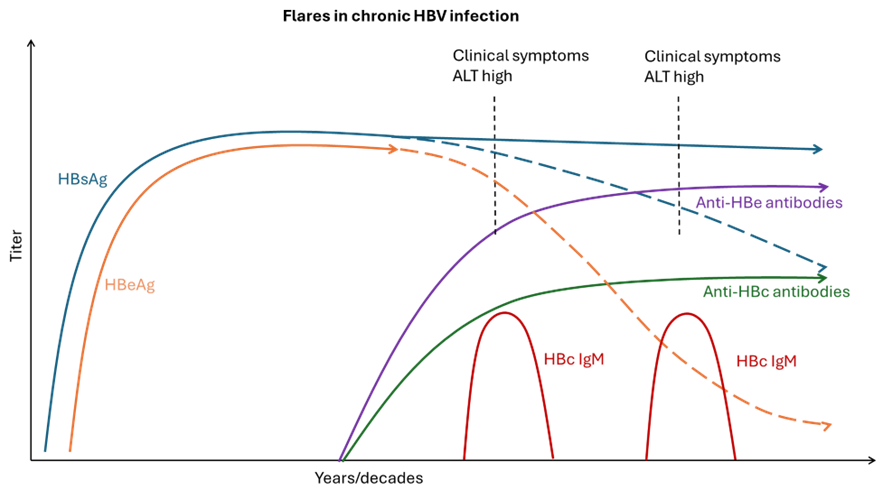

The clinical symptoms of viral hepatitis caused by different viruses are not discriminatory and cannot distinguish any pathogen, meaning that laboratory diagnosis is required to identify an HBV infection. Different markers of infection have been identified to assess the status of either an acute or chronic infection (see below). In addition, clinical measures, such as ultrasound, fibroscan or biopsy analyse the level of fibrosis and monitor the progression of the liver disease. The markers for infection and clinical parameters are important tools for treatment success monitoring (Table 3, Figures 4-6). More information is available from WHO Guidelines on hepatitis B and C testing and Guidelines for the prevention, diagnosis, care and treatment for people with chronic hepatitis B infection [9,23].

Markers of infection [9,23] are:

HBsAg: hepatitis B surface antigen

The presence of this serological marker signifies HBV infection. HBsAg testing is commonly used for HBV infection screening to diagnose chronic and acute HBV infections. HBsAg is an antigen on the envelope of the HBV virion and usually becomes detectable during weeks 4–10 after infection. Chronic infection is usually defined as the persistence of HBsAg for more than six months. HBsAg is not detectable in occult infections (HBV DNA presence).

Anti-HBs: antibody to hepatitis B surface antigen

This is a neutralising antibody indicating protection from infection after vaccination (no anti-HBc detectable) and successful resolution of acute infection. A positive test indicates that the person has immunity to the virus, either through vaccination or after recovering from the virus. This indicates that the person cannot be infected with hepatitis B again. Following a course of vaccination against hepatitis B, serological testing for anti-HBs can be used as a proxy for protection with anti-HBs levels of 10 mIU/mL or greater, shown to strongly correlate with protection against HBV. However, levels of anti-HBs do wane over time and are not always good correlates of protection, as someone with low levels of antibodies several years after vaccination may still be able to mount a strong immune response that protects against hepatitis B.

Anti-HBc: antibody to hepatitis B core antigen

Anti-HBc is an antibody to a peptide of the core protein. Anti-HBc immunoglobulin G (IgG) (anti—HBc IgG) remains positive for life after exposure to HBV but, unlike anti-HBs, anti-HBc is not a protective antibody. During acute infection, anti-HBc immunoglobulin M (IgM) (anti-HBc IgM) is found in high concentrations which reduce over 3–6 months, while anti-HBc IgG increases. Anti-HBc IgM is commonly used to differentiate between acute and chronic infection but is unreliable for identification of recent primary HBV infection alone as low-grade elevations may also occur during ‘flares’ in chronic disease progression.

HBeAg: Hepatitis B ‘e’ antigen

The hepatitis B envelope antigen (HBeAg) is found between the core and lipid envelope and is present in both acute and chronic infection. The presence of HBeAg is often associated with high levels of viral replication and increased transmissibility. The marker is often used during assessment for treatment of chronic HBV infection (together with ALT level).

Anti-HBe: Antibody to hepatitis B e antigen

Anti-HBe is not a protective antibody. However, the appearance of anti-HBe often occurs following a major immunological change when there are lower levels of HBV DNA. The loss of HBeAg and the development of anti-HBe is called ‘HBeAg seroconversion’ and is usually associated with a lower risk of disease progression.

HBV DNA: Hepatitis B virus genome

Measurement of HBV DNA through molecular amplification methods such as PCR enables a quantification of HBV viral replication. HBV DNA monitoring is now a core part of HBV clinical management. HBV DNA is very dynamic during chronic HBV infections and is a strong correlate of disease progression and the development of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. HBV DNA is also a marker of infectivity and is used to assess antiviral treatment response. It is detectable early in infection (before HBsAg) and can be used for diagnosis in those at-risk or in outbreaks.

No single marker is sufficient for the assessment and serial monitoring of serum HBeAg, HBV DNA and ALT levels is recommended [9,14].

Figure 4. Acute HBV infection with clearance of the virus

Adapted from S. Ijaz (UKHSA) and WHO Guidelines on hepatitis B and C testing [9]

Figure 5. Chronic HBV infection with persistence of the virus

Adapted from S. Ijaz (UKHSA) and WHO Guidelines on hepatitis B and C testing [9]

Figure 6. Flares in chronic HBV infections

Adapted from S. Ijaz (UKHSA) and WHO Guidelines on hepatitis B and C testing [9]

The following specimen types are best suited to testing for the different HBV markers:

Serum/plasma:

- All HBV antigens

- All antibodies to HBV

- HBV DNA

- HBV sequence information.

Oral fluid (not saliva)

- HBsAg

- Anti-HBc.

Dried blood spots (DBS)

- HBsAg

- Anti-HBc

- HBV DNA and sequence.

Case management and treatment

Treatment of acute hepatitis B virus infection aims to alleviate symptoms.

Different oral antivirals are available for the treatment of chronic hepatitis B and treatment generally has to be taken for life due to the fact that HBV integrates into the genome and therefore requires viral replication to be continuously suppressed.

EU authorised nucleoside/nucleotide analogues (NAs) for HBV treatment include [24-31]:

- Lamivudine (LAM) - associated with a low barrier to HBV resistance

- Entecavir (ETV) - associated with a high barrier to HBV resistance

- Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) - associated with a high barrier to HBV resistance

- Tenofovir alafenamide (TAF) - associated with a high barrier to HBV resistance.

Treatment aims to lower viral replication and thereby reduce the viral load to slow down the liver damage and even help in regression of fibrosis and cirrhosis, advancing restoring functions in chronic hepatitis B patients.

Treatment is an important component to preventing mother-to-child transmission, and virus reactivation.

For further details of treatment recommendations please consult the guidelines of The European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) 2025 [32], which propose a simplified treatment algorithm independent of the HBeAg status of the patient, and recommendations for disease assessment in HBsAg-positive individuals. The guidance recommends treatment for ‘patients with HBeAg-positive or HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B, HBV DNA level ≥2,000 IU/ml and elevated ALT (>ULN) and/or significant fibrosis should receive antiviral therapy’ [32].

Public health prevention and control measures

Hepatitis B virus infection can be prevented by a safe and highly effective vaccine. In the EU, single and multivalent combination vaccines that include hepatitis B are authorised [33-40]. Some of the vaccines are authorised for use only in adults or children while other vaccines also include antigens that are added for protection against other infections, such as the hepatitis A virus.

The hepatitis B vaccine is the mainstay of hepatitis B prevention. Safe and effective vaccines are available that offer high levels of protection and most countries in Europe have implemented a universal HBV vaccination programme during early childhood in their routine childhood vaccination schedule. Vaccination schedules vary across countries, but HBV vaccination is commonly provided as a series of three doses, generating long-lasting protection against hepatitis B.

With evidence of ongoing transmission and continuing importation of cases, these vaccination programmes are essential in order to achieve the target of hepatitis elimination by 2030.

In addition to vaccination programmes, transmission of HBV infection can be reduced by:

- safe sex, using condoms and reducing the number of sexual partners;

- harm reduction measures for people who inject drugs, including safe injection practices and the use of opioid agonist therapy for opiate users;

- use of sterile needles and equipment during any invasive procedure, including piercing or tattooing;

- strict enforcement of infection prevention and control measures in healthcare settings;

- blood safety strategies, including the testing of substances of human origin (e.g. blood donations).

Mother-to-child transmission can be prevented through antenatal screening of pregnant women and antiviral treatment of HBV positive mothers, as well as immunoglobulin administration for newborns (where indicated) together with vaccination, starting at birth. Authorised immunoglobulins are available in the EU [41].

Antiviral treatment is an effective measure to suppress the viral load and infectiousness of people with HBV infection, thereby reducing the risk of further transmission − e.g. for the prevention of mother-to-child-transmission [42]. For further details see The European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) publication from 2025 [32].

HBV is included in the WHO Regional action plans for ending AIDS and the epidemics of viral hepatitis and sexually-transmitted infections 2022–2030 with an elimination target [11]. By 2030, a 90% reduction in the number of new chronic hepatitis B infections and a 65% reduction in the number of deaths is to be achieved (Table 4) [11]. ECDC has developed a monitoring framework that describes the building blocks and actions to support the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) on health target 3.3, with a focus on HIV/AIDS, viral hepatitis, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and tuberculosis (TB) (SDG goal 3.3 and corresponding global targets) [43].

Table 4. Selected areas included in the 2025 interim and 2030 elimination target [11]

| Target areas (selected) | 2025 interim | 2030 target |

|---|---|---|

| Vaccination coverage hepatitis B vaccine for infants (3-dose) | 95% | 95% |

| Prevention of mother-to-child transmission: HBV vaccination at birth or other approaches | 90% | 95% |

| Percentage of pregnant women screened for HBsAg | 90% | 95% |

| Blood donation screening | 100% | 100% |

| Distribution of sterile needle/syringe per person for people who inject drugs (PWID) per year | 200 | 300 |

| Diagnosis of HBV | 60% | 90% |

| Treatment of HBV | 50% eligible treated | 80% eligible treated |

Advice to travellers

Disclaimer: Travel health physicians and travellers should always first consult national travel guidelines and recommendations as the primary source of information.

Hepatitis B has a varied global distribution (Figure 1) with areas of high and lower prevalence. Hepatitis B vaccination protects from travel-acquired infections and could be considered for unvaccinated individuals before travelling.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Introduction to the Annual Epidemiological Report In: ECDC. Annual epidemiological report Stockholm: ECDC; 2022. Available from: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/surveillance-and-disease-data/annual-epidemiological-reports/introduction-annual

- European Commission (EC). Commission implementing decision of 8 August 2012 amending Decision 2002/253/EC laying down case definitions for reporting communicable diseases to the Community network under Decision No 2119/98/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council (2012/506/EU) (notified under document C(2012) 5538) (Text with EEA relevance) (2012/506/EU) – Annex 2.17 Hepatitis B (Hepatitis B virus) Brussels: European Commission,; 2012 [cited 7 Feb 2024]

- European Commission (EC). Commission implementing decision (EU) 2018/945 of 22 June 2018 on the communicable diseases and related special health issues to be covered by epidemiological surveillance as well as relevant case definitions. Brussels: European Commission; 2018 [cited 10 Jan 2024]. Available from: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32018D0945

- Hsu YC, Huang DQ, Nguyen MH. Global burden of hepatitis B virus: current status, missed opportunities and a call for action. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Aug;20(8):524-37.

- International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Official Taxonomic Resources: International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses: ICTV; 2025. Available from: https://ictv.global/taxonomy.

- Lin CL, Kao JH. Hepatitis B virus genotypes and variants. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2015 May 1;5(5):a021436.

- Lavanchy D. Hepatitis B virus epidemiology, disease burden, treatment, and current and emerging prevention and control measures. J Viral Hepat. 2004 Mar;11(2):97-107.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Hepatitis B in the WHO European Region Copenhagen: WHO; 2022 [cited 10 Jan 2024]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hepatitis-b

- World Health Organization (WHO). Guidelines on hepatitis B and C testing. Geneva: WHO. 16 February 2017. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241549981

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global progress report on HIV, viral hepatitis and sexually transmitted infections, 2021 Geneva: WHO; 2021 [cited 10 Jan 2024]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240027077

- World Health Organization (WHO). Regional action plans for ending AIDS and the epidemics of viral hepatitis and sexually transmitted infections 2022–2030. Copenhagen: WHO, 14 June 2023. Available from: https://www.who.int/europe/publications/i/item/9789289058957

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global hepatitis report 2024: action for access in low- and middle-income countries. WHO, 9 April 2024. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240091672

- Australasian Society for HIV Medicine (ASHM). B Positive, Hepatitis B for primary care - A guide for primary care providers 2022. Available from: https://hepatitisb.org.au/

- European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL). 2017 Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2017 Aug;67(2):370-98.

- Feng G, Yilmaz Y, Valenti L, Seto WK, Pan CQ, Méndez-Sánchez N, et al. Global Burden of Major Chronic Liver Diseases in 2021. Liver Int. 2025 Apr;45(4):e70058.

- Polaris Observatory Collaborators. Global prevalence, cascade of care, and prophylaxis coverage of hepatitis B in 2022: a modelling study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Oct;8(10):879-907.

- Hofstraat SHI, Falla AM, Duffell EF, Hahné SJM, Amato-Gauci AJ, Veldhuijzen IK, et al. Current prevalence of chronic hepatitis B and C virus infection in the general population, blood donors and pregnant women in the EU/EEA: a systematic review. Epidemiol Infect. 2017 Oct;145(14):2873-85.

- Bivegete S, McNaughton AL, Trickey A, Thornton Z, Scanlan B, Lim AG, et al. Estimates of hepatitis B virus prevalence among general population and key risk groups in EU/EEA/UK countries: a systematic review. Euro Surveill. 2023 Jul;28(30).

- Mårdh O, Quinten C, Amato-Gauci AJ, Duffell E. Mortality from liver diseases attributable to hepatitis B and C in the EU/EEA - descriptive analysis and estimation of 2015 baseline. Infect Dis (Lond). 2020 Sep;52(9):625-37.

- Finatto-Canabarro A, Niehus R, Champezou L, Marrone G, Duffell E. Estimation of the number of individuals infected with chronic hepatitis B infection in EU/EEA countries using the workbook method. [Submitted].

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Prevention of hepatitis B and C in the EU/EEA, 2024. Stockholm: ECDC, 2024. Available from: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/prevention-hepatitis-b-and-c-eueea-2024

- US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Haber P, Schilie S. Chapter 10: Hepatitis B. 2021.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Guidelines for the prevention, diagnosis, care and treatment for people with chronic hepatitis B infection. Geneva: WHO, 2024. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240090903

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). Pegasys peginterferon alfa-2a 2002. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/pegasys

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). Viread tenofovir disoproxil 2002. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/viread

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). Lamivudine Teva lamivudine 2009. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/lamivudine-teva

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). Zeffix lamivudine 2016. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/zeffix

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). Entecavir Viatris (previously Entecavir Mylan) 2017. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/entecavir-viatris

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). Entecavir Accord entecavir 2017. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/entecavir-accord

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). Vemlidy tenofovir alafenamide 2017. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/vemlidy

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). Baraclude - entecavir 2020. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/baraclude

- Cornberg M, Sandmann L, Jaroszewicz J, Kennedy P, Lampertico P, Lemoine M, et al. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of hepatitis B virus infection. Journal of Hepatology. 10 May 2025. J Hepatol. 2025 Aug;83(2):502-583.

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). Twinrix Paediatric - hepatitis A (inactivated) and hepatitis B (rDNA) (HAB) vaccine (adsorbed) 2008. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/twinrix-paediatric

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). Twinrix Adult - hepatitis A (inactivated) and hepatitis B (rDNA) (HAB) vaccine (adsorbed) 2008. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/twinrix-adult

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). Ambirix - hepatitis A (inactivated) and hepatitis B (rDNA) (HAB) vaccine (adsorbed) 2008. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/ambirix

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). HBVaxPro hepatitis B vaccine (recombinant DNA) 2008. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/hbvaxpro

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). Infanrix Hexa - diphtheria (D), tetanus (T), pertussis (acellular, component) (Pa), hepatitis B (rDNA) (HBV), poliomyelitis (inactivated) (IPV) and Haemophilus influenzae type-b (Hib) conjugate vaccine (adsorbed) 2008. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/infanrix-hexa

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). Fendrix hepatitis B (rDNA) vaccine (adjuvanted, adsorbed) 2009. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/fendrix

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). Hexacima - diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis (acellular, component), hepatitis B (rDNA), poliomyelitis (inactivated) and Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate vaccine (adsorbed) 2013. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/hexacima

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). Vaxelis - diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis (acellular, component), hepatitis B (rDNA), poliomyelitis (inactivated) and Haemophilus type b conjugate vaccine (adsorbed) 2016. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/vaxelis

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). Zutectra human hepatitis B immunoglobulin 2010. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/zutectra

- World Health Organization (WHO). Hepatitis: Preventing mother-to-child transmission of the hepatitis B virus: WHO; 2020 [May 2025]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/hepatitis-preventing-mother-to-child-transmission-of-the-hepatitis-b-virus

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Framework for action on the Sustainable Development Goal diseases. Stockholm: ECDC; 2024. Available from: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/ecdc-framework-action-sustainable-development-goal-diseases