Epidemiological update: COVID-19 transmission in the EU/EEA, SARS-CoV-2 variants, and public health considerations for Autumn 2023

Key messages

- In recent weeks, signals of SARS-CoV-2 transmission have increased from previously very low levels in the EU/EEA. Factors unrelated to the genetic evolution of SARS-CoV-2 likely contributed to observed increases in epidemiological indicators, such as large gatherings and increased travel during the seasonal holidays, as well as waning levels of immunological protection against infection – but not severe disease – in the population.

- Nonetheless, SARS-CoV-2 remains capable of acquiring mutations that facilitate its continued circulation at unpredictable times throughout the year. Recently observed increases in SARS-CoV-2 transmission have coincided with the emergence and subsequent dominance of a group of related Omicron sub-lineages, XBB.1.5-like variants carrying the F456L mutation.

- In August 2023, sporadic detections of a new highly mutated Omicron sub-lineage, BA.2.86, were reported within and outside the European Union/European Economic Area (EU/EEA). Although very few case detections have been confirmed globally, low-level community transmission of this variant is suspected in multiple countries. In terms of mutations, the variant is highly divergent from currently circulating SARS-CoV-2 variants bringing the possibility of increased reinfections if it successfully outcompetes currently circulating variants in the EU/EEA.

- There is no indication that infection with XBB.1.5-like+F456L variants or BA.2.86 are associated with more severe disease or a reduction in vaccine effectiveness against severe disease when compared to currently circulating variants. Older people and those with underlying conditions remain at increased risk of severe outcomes if infected.

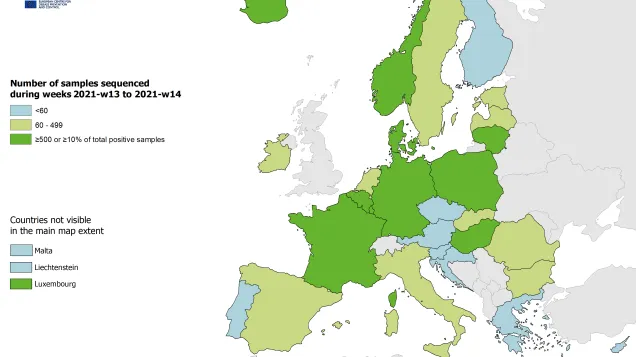

- The completeness and timeliness of epidemiological and virological COVID-19 surveillance data in the EU/EEA has decreased significantly in the past year. The emergence of BA.2.86 underscores the importance of continued vigilance for SARS-CoV-2 by strengthening representative surveillance systems in primary and secondary care to detect trends in COVID-19 transmission and severe disease. Where possible, all SARS-CoV-2-positive specimens from representative surveillance systems should be sequenced and reported to the Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data (GISAID) and/or The European Surveillance System (TESSy) to facilitate the continued assessment of circulating variants.

- Vaccination efforts should focus on protecting those at risk of progression to severe disease, e.g. people aged over 60 years and other vulnerable individuals irrespective of age (such as people with underlying comorbidities or immunocompromised conditions). As we approach autumn vaccination campaigns, countries should carefully consider factors that have previously limited booster vaccine uptake and address them. So that vaccination campaigns adequately protect population groups that remain at risk of severe COVID-19 disease, countries should assess their readiness to detect and respond to epidemiological signals of increased COVID-19 transmission. They should also assess their ability to identify and reach high-risk groups. Communication campaigns that engage healthcare professionals and the wider public play a critical role in highlighting the importance of staying up to date with COVID-19 vaccination for high-risk groups

The COVID-19 epidemiological situation in the EU/EEA as of 27 August 2023

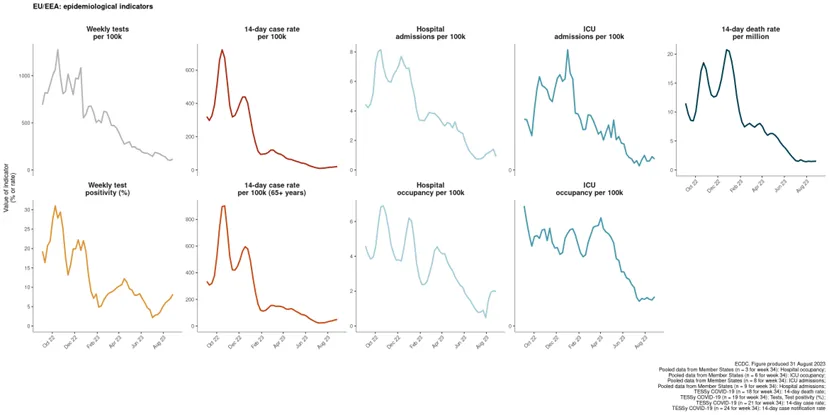

Data reported to ECDC by the end of week 34 (ending 27 August 2023) suggest that transmission of SARS-CoV-2 is increasing in the EU/EEA region (Figure 1) [1]. Current data availability, especially regarding disease severity, is limited, and the overall assessment of the impact and severity of disease in the EU/EEA should therefore be interpreted with caution.

Pooled data based on information from comprehensive surveillance systems from 24 countries show a rise in 14-day case rate, albeit with a very limited growth. The magnitude of the observed increase is far lower than previous epidemic peaks, but this information should be interpreted taking into account changes in COVID-19 testing strategies across countries, along with a large reduction in the number of tests performed compared to during other epidemic periods.

Among 21 countries that reported age-specific data on cases positive for COVID-19, 14 observed increases in case rates among people aged 65 years and above, and 16 observed increases in case rates among people aged 80 years and above. As these age groups have the highest risk of severe disease, these figures highlight the importance of continuing to monitor disease and protecting older age groups.

Test positivity has increased in 12 out of 19 countries reporting information, but scaled down testing or testing limited to particular settings instead of universal testing may introduce bias in positivity figures.

All 10 countries with data on hospital or ICU admissions/occupancy up to week 34 reported stable trends compared with the previous week. In total, 135 deaths were reported by 18 countries (compared with 52 deaths reported by 15 countries in the previous week), with two countries reporting increases in their death rates. Three countries observed increasing death rates in the 65 years and above age group. The reported increases are of short duration (of one to two weeks) and current levels remain very low relative to previous peaks reported during the pandemic.

At country level, the number of patients presenting to sentinel general practitioners with respiratory illness (influenza-like illness /acute respiratory infection) remain at low levels compared to the winter season, and in line with those observed during the same period last year.

The availability of sentinel data on severe COVID-19 disease is limited, but so far these data suggest minimal impact on severity. None of the four countries reporting data from severe acute respiratory infections (SARI) sentinel surveillance up to week 34 observed elevated rates of SARI hospitalisations.

Factors contributing to increased SARS-CoV-2 transmission

Several factors that are not attributable to the virus may contribute to observed increases in epidemiological indicators for COVID-19 transmission. Large gatherings and increased travel during the seasonal holidays can contribute to increased mixing and the likelihood of transmission. After several months of very low disease incidence, levels of immunological protection against infection – but not severe disease – may have also declined.

Although seasonal changes in population mixing contribute to increased SARS-CoV-2 transmission, transmission does not yet follow a predictable seasonal pattern. SARS-CoV-2 remains capable of acquiring mutations that facilitate its continued circulation at unpredictable times throughout the year. Recently observed increases in SARS-CoV-2 transmission have coincided with the emergence and subsequent dominance of a group of related Omicron sub-lineages, XBB.1.5-like variants carrying the F456L mutation. In August 2023, sporadic detections of a new Omicron sub-lineage, BA.2.86, were also reported within and outside the EU/EEA. This variant is highly divergent from currently circulating SARS-CoV-2 lineages, with potential implications for reinfections in the EU/EEA population.

SARS-CoV-2 variants

The global SARS-CoV-2 variant landscape is currently characterised by XBB descendant lineages. XBB originated from a recombination event that likely occurred between two co-circulating Omicron BA.2 lineages (BJ.1 and BM.1.1.1) [2]. XBB was first detected in September 2022 and became a very successful lineage. Over 300 XBB descendant lineages have been described so far [3], which carry additional mutations on top of the original XBB backbone. The global variant landscape was dominated until recently by a group of XBB lineages characterised by the presence of three mutations in the Spike protein (N460K, S486P, F490S), termed XBB.1.5-like variants. However, a new group of XBB.1.5-like variants carrying the F456L mutation (XBB.1.5-like+F456L) is currently replacing XBB.1.5-like lineages in most regions of the world.

XBB.1.5-like+F456L variants

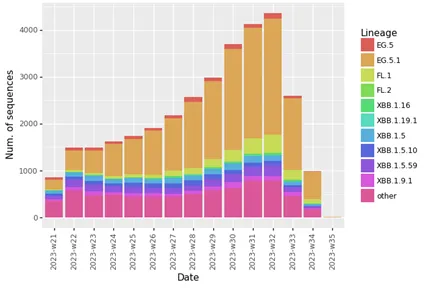

The XBB.1.5-like umbrella comprises several distinct lineages that are all descendants of XBB. Among these, there are XBB.1.5, XBB.1.9.1, XBB.1.9.2, XBB.1.16, and XBB.2.3. Several different sub-lineages within these have now acquired the additional spike protein change F456L, which confers a selective advantage over previously circulating variants. XBB.1.5-like+F456L variants are characterised by spike protein receptor-binding domain changes F456L, N460K, S486P, and F490S. EG.5.1 (XBB.1.9.2.5.1) is the most common lineage within the XBB.1.5-like+F456L group globally (Figure 2).

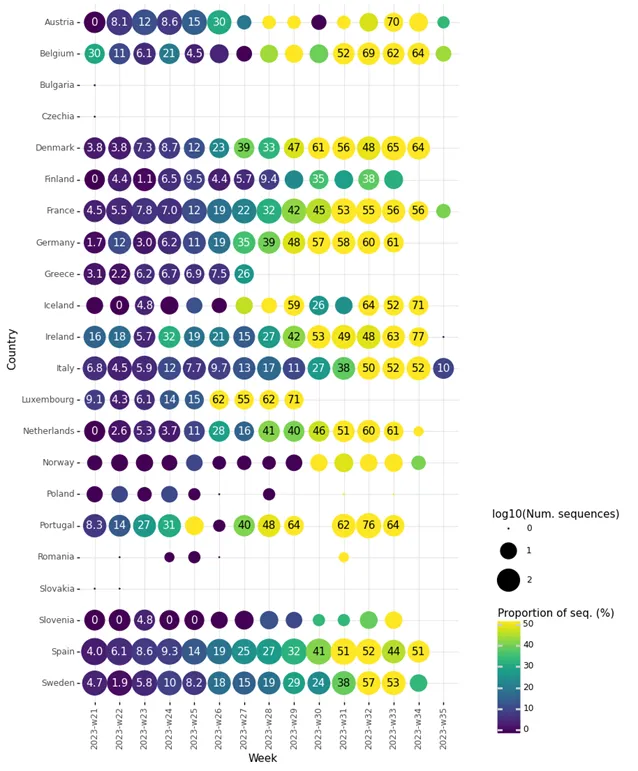

In the EU/EEA, amongst countries reporting at least 10 sequences to GISAID EpiCoV for week 33 (14 August to 20 August 2023) the following proportions of XBB.1.5-like+F456L lineages were observed: Austria (70%), Belgium (62%), Denmark (65%), France (56%), Germany (61%), Iceland (52%), Ireland (63%), Italy (52%), the Netherlands (61%), Portugal (64%), Spain (44%), and Sweden (53%). Data suggest that XBB.1.5-like+F456L lineages are currently the dominant SARS-CoV-2 lineages in many EA/EEA countries (Figure 3).

ECDC SARS-CoV-2 variant classification criteria and recommended actions for EU/EEA Member States are outlined on the ECDC variant webpage [4,5]. As of 10 August 2023, ECDC classified all XBB.1.5-like lineages with the additional spike protein change F456L as SARS-CoV-2 variants of interest (VOI). The reasons for this classification are: a) the rapid increase in the proportion of this mutation in the positive samples from EU/EEA countries, b) a slight increase in epidemiological indicators of community transmission, and c) the mutation is predicted and verified by a preliminary in-vitro study to contribute to immune escape, compared to previously circulating variants [6]. So far there is no evidence that F456L variants meet any of the criteria for variants of concern (VOC), i.e. moderate to high evidence of the variant being associated with an increase in infection severity, a risk for compromising the healthcare capacity in the EU/EEA, or a reduction in vaccine effectiveness against severe disease.

BA.2.86

First detected in mid-August 2023, BA.2.86 is characterised by spike protein receptor-binding domain changes I332V, D339H, R403K, V445H, G446S, N450D, L452W, N481K, 483del, E484K, and F486P.

BA.2.86 is thought to be a descendent of BA.2, which emerged in December 2021 before subsequent replacement by other Omicron sub-lineages by August 2022, although some of its descendent lineages (CH.1.1) were still circulating in September 2023. BA.2.86 features over 30 mutations that are distinct from ancestral BA.2 and currently circulating XBB-derived variants. A plausible hypothesis for the sudden emergence of such a highly divergent variant is that it may have evolved under antibody pressure in an immunocompromised patient experiencing a chronic infection with a BA.2-derived variant, however, this is difficult to confirm [7,8].

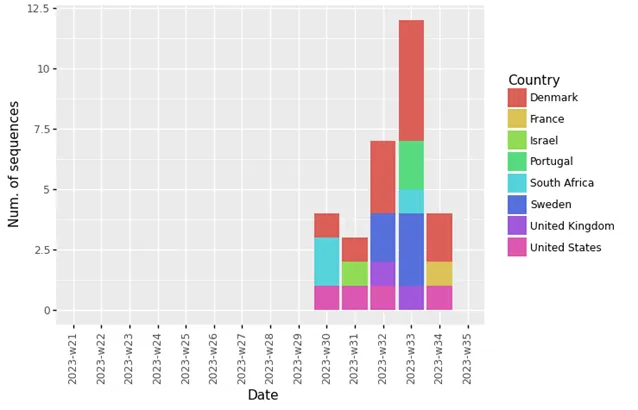

Globally, as of 4 September 2023, 30 cases of BA.2.86 have been reported to GISAID from 8 countries (Figure 4). In the EU/EEA, these were Denmark (12), France (1), Portugal (2) and Sweden (5). Outside the EU/EEA, these were Israel (1), South Africa (3), the UK (2), and the US (4). Detection of this variant has been reported in wastewater samples from several more countries, both within and outside the EU/EEA.

Unpublished phylodynamic analysis indicates that BA.2.86 emerged recently, between May and July 2023 [9]. Given that by August 2023 BA.2.86 has been detected in several countries in different regions, with no known epidemiological link to a common source, it may be associated with an elevated growth rate compared to current circulating variants, although this is associated with a high degree of uncertainty. The mechanism of any growth advantage likely includes immune escape, as BA.2.86 carries many spike changes compared with XBB.1.5-like variants that have dominated recently, as well as compared with previous Omicron variants.

As of 24 August, ECDC has classified BA.2.86 as a variant under monitoring (VUM) because of a high number of spike protein mutations that were predicted to evade vaccine-induced immunity against SARS-CoV-2 infection [10]. It is still too early to confirm that these mutations confer a growth advantage for BA.2.86, and it is not yet possible to predict the impact of these mutations on the variant’s transmission fitness relative to currently circulating XBB-derived variants. Across the EU/EEA, the vast majority of the population has developed hybrid immunity through a combination of vaccination and at least one prior infection. Preliminary pseudovirus neutralisation studies for BA.2.86 show that serum from individuals with hybrid immunity—particularly following booster vaccination and infection with recent XXB-derived variants—is able to effectively neutralise BA.2.86 in vitro, indicating that a combination of hybrid immunity coupled with recent infection confers some protection against BA.2.86 infection [11,12].

It is unlikely that BA.2.86 variants are associated with any increase in infection severity compared to currently circulating variants, or a reduction in vaccine effectiveness against severe disease. However, older individuals and those with underlying conditions remain at increased risk of severe outcomes, if infected. Given the very limited number of confirmed BA.2.86 detections globally, epidemiological studies to formally assess severity and vaccine effectiveness relative to other circulating variants are not yet available.

Public health actions

Monitoring and reporting

Current data availability makes it challenging to assess the COVID-19 epidemiological situation in the EU/EEA. Although some countries have continued with primary care syndromic surveillance this summer, the low levels of testing in these settings add substantial uncertainty to estimates of SARS-CoV-2 positivity. SARI surveillance has been expanded in the EU/EEA but is still limited to relatively few countries. As of week 34, only one third of the countries reported data on admissions to hospital or ICU, and around half reported data on COVID-19 deaths. These figures can still be a useful complement to data from sentinel systems, but must be treated with some caution. The lack of a standardised case definition in respiratory infections’ syndromic surveillance systems across countries and potential for changes in underlying strategies for testing and reporting can introduce bias or artefact. The reduction in PCR testing and low levels of transmission over the summer has also led to very limited volumes of sequencing, which limits ECDC’s ability to assess variants.

As outlined in the guidance document, ‘Operational considerations for respiratory virus surveillance in Europe’ [1], EU/EEA Member States are encouraged to expand their use of, and report data from well-designed, representative population-based surveillance in primary and secondary care to monitor trends in transmission and severe disease. Where possible, all SARS-CoV-2-positive specimens from representative surveillance systems should be sequenced and reported to GISAID and/or TESSy to facilitate the assessment of circulating variants.

Vaccination

Based on ECDC’s interim public health considerations for COVID-19 vaccination roll-out during 2023, vaccination efforts should focus on protecting those aged over 60 years and other vulnerable individuals irrespective of age (such as those individuals with underlying comorbidities and individuals with immunocompromised conditions). In addition, mathematical modelling indicated that an autumn 2023 vaccination campaign (with an optimistic scenario of high vaccine uptake among individuals aged 60 years and above) is expected to prevent an estimated 21–32% of the cumulative total all-age COVID-19 related hospitalisations across EU/EEA countries until 28 February 2024 [13].

In the EU/EEA, the COVID-19 vaccine uptake has been monitored since the start of the vaccination campaign in December 2020 [14]. As of August 2023, 84.9% (range: 13.6–100%) of the population aged 60 years and above (60+) in EU/EEA countries has received a first booster dose (with differences of uptake across countries), with the majority of countries (n=17) reporting national uptakes above 80% in this age group. For the second booster dose, 35.6% (range: 0.4–87.1%) of the population aged 60 years and above has received a second booster dose, with most countries (n=20) reporting national uptakes below 50% in this age group. In the EU/EEA, based on 23 countries reporting, 4% (range: <0.1–47.2%) of the population aged 60 years and above has received a third booster dose, with all countries reporting an uptake of below 50% in this age group. Overall, the vaccine uptake of the first booster dose levelled off in autumn 2021 and is very high in the EU/EEA, with the majority of countries reporting vaccine uptakes over 80% for the first booster dose. However, this situation differs for the second booster dose, with the majority of countries still not reaching 50% of vaccine uptake in this age group.

Several EU/EEA countries have published their recommendations for COVID-19 autumn vaccination campaigns. The age cut-offs indicated differ between countries. In some countries, vaccination is recommended to the same age group as the annual influenza vaccination. Other high-risk groups recommended vaccination include persons aged six months and older with underlying diseases (i.e. chronic respiratory, cardiovascular, liver and kidney disease, diabetes, obesity, chronic neurological disease, immunosuppression) and residents in long-term care facilities.

On 30 August 2023, EMA’s human medicines committee (CHMP) recommended authorising an adapted Comirnaty vaccine targeting the Omicron XBB.1.5 subvariant [15]. According to the recommendation for authorisation, adults and children aged from five years who require vaccination should have a single dose, irrespective of their COVID-19 vaccination history. Children aged between six months and four years who require vaccination may have one or three doses depending on whether they have completed a primary vaccination course or have had COVID-19. The European Commission authorised the Comirnaty XBB.1.5-adapted COVID-19 vaccine on 1 September 2023 [16].

In the current setting, countries should carefully consider factors that have previously limited booster vaccine uptake and address them as we approach autumn vaccination campaigns. So that vaccination campaigns adequately protect population groups that remain at risk of severe COVID-19 disease, countries should assess their readiness to detect and respond to epidemiological signals of increased COVID-19 transmission. Due to the evolving COVID-19 epidemiology in the EU/EEA, the timely identification of vaccination campaign target groups is essential to protect people at a high risk for severe disease and death. Communication campaigns providing clear information through trusted channels and messengers regarding which groups vaccination is recommended to, why vaccination is important, and the timing of them are all key to improving vaccine uptake [13]. This should include engagement with healthcare workers, as they are trusted sources regarding information on vaccination. Strategies to facilitate access to vaccination services should also be considered.

Consulted experts (in alphabetical order)

Ana Torres, Jordi Borrell Pique, Orlando Cenciarelli, Luca Freschi, Kate Olsson, Ajibola Omokanye, Theodora Stavrou, Andrea Würz.

References

1. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Country overview report: week 34 2023. Stockholm: ECDC; 2023. Available at: https://covid19-country-overviews.ecdc.europa.eu/index.html

2. Tamura T, Ito J, Uriu K, Zahradnik J, Kida I, Anraku Y, et al. Virological characteristics of the SARS-CoV-2 XBB variant derived from recombination of two Omicron subvariants. Nature communications. 2023;14(1):2800. Available at: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-023-38435-3

3. Github. CoV-lineages/pango-designation. 2023. Available at: https://github.com/cov-lineages/pango-designation

4. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern as of 10 August 2023. Stockholm: ECDC; 2023. Available at: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/covid-19/variants-concern

5. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). ECDC SARS-CoV-2 variant classification criteria and recommended EU/EEA Member State actions. Stockholm: ECDC; 2023. Available at: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/ECDC%20SARS-CoV-2%20variant%20classification%20criteria%20and%20recommended%20Member%20State%20actions.pdf

6. Ayijiang Y, Weiliang S, Jing W, Fanchong J, Yuanling Y, Xiaosu C, et al. Repeated Omicron exposures override ancestral SARS-CoV-2 immune imprinting. bioRxiv [Preprint]. 2023. DOI: 10.1101/2023.05.01.538516. Available at: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2023.05.01.538516v4

7. Chaguza C, Hahn AM, Petrone ME, Zhou S, Ferguson D, Breban MI, et al. Accelerated SARS-CoV-2 intrahost evolution leading to distinct genotypes during chronic infection. Cell Reports Medicine. 2023;4(2) Available at: https://www.cell.com/cell-reports-medicine/pdf/S2666-3791(23)00035-6.pdf

8. Raglow Z, Surie D, Chappell JD, Zhu Y, Martin ET, Kwon JH, et al. SARS-CoV-2 shedding and evolution in immunocompromised hosts during the Omicron period: a multicenter prospective analysis. medRxiv [Preprint]. 2023. DOI: 2023.08.22.23294416. Available at: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2023.08.22.23294416.abstract

9. Nextstrain.org. Phylogenetic analysis of BA.2.86 diversity. 2023. Available at: https://nextstrain.org/groups/neherlab/ncov/BA.2.86?m=num_date

10. EVEscape. Biweekly Variant Report 25/08/2023. Emerging variant BA.2.86 predicted to have significant antibody escape with up to 21- and 26-fold decrease in neutralizing titers relative to CH.1.1 and XBB.1.5, respectively. Available at: https://evescape.org/data

11. Yang S, Yu Y, Jian F, Song W, Yisimayi A, Chen X, et al. Antigenicity and infectivity characterization of SARS-CoV-2 BA.2.86. bioRxiv [Preprint]. 2023. DOI: 10.1101/2023.09.01.555815. Available at: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/biorxiv/early/2023/09/04/2023.09.01.555815.full.pdf

12. Sheward DJ, Yang Y, Westerberg M, Öling S, Muschiol S, Sato K, et al. Sensitivity of BA.2.86 to prevailing neutralising antibody responses. bioRxiv [Preprint]. 2023. DOI: 10.1101/2023.09.02.556033. Available at: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/biorxiv/early/2023/09/04/2023.09.02.556033.full.pdf

13. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Interim public health considerations for COVID-19 vaccination roll-out during 2023. Stockholm: ECDC; 2023. Available at: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/interim-public-health-considerations-covid-19-vaccination-roll-out-during-2023

14. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). COVID-19 Vaccine Tracker. Stockholm: ECDC; 2023. Available at: https://vaccinetracker.ecdc.europa.eu/public/extensions/COVID-19/vaccine-tracker.html#summary-tab

15. European Medicines Agency (EMA). Comirnaty: EMA recommends approval of adapted COVID-19 vaccine targeting Omicron XBB.1.5. Amsterdam: EMA; 2023. Available at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/comirnaty-ema-recommends-approval-adapted-covid-19-vaccine-targeting-omicron-xbb15

16. European Commission (EC). COVID-19: Commission authorises adapted COVID-19 vaccine for Member States' autumn vaccination campaig. Brussels: EC; 2023. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_23_4301